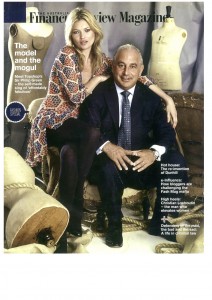

KISS AND SELL. SIR PHILIP GREEN

by Marion Hume

The AFR Magazine September 2010

The self-made king of affordably fabulous has the retail touch: Sir Philip Green ships about 150 million garments a year through ‘cheap chic’ outlets such as the Topshop chain. He’s worth about $7.6 billion and is still working

on how his businesses can adjust to a new consumer embracing social media

Sir Philip Green doesn’t waste time. My allotted slot with the global king of affordable chic is at 1 o’clock, and at 12.59pm, after ice water and coffee has been served in the plush reception area outside his office (pale carpets, swanky sofas, Jo Malone scent in the loo), the door swings open and here he is; pin-neat grey suit, pristine white shirt open at the neck. Two buttons, no tie; silver swept-back hair shimmering with the sheen of a shampoo commercial; tanned skin positively glowing. In other words, the absolute picture of a 58-year-old, self-made man worth about £4.43billion ($7.6billion), whose Monday morning commute from the family home is by private jet from The French Riviera.

Green is famous for the fact he pulls no punches and answers his own phone (not some new-fangled device but an old Nokia; he has a stockpile of them). Want to know about the ethics of the rag trade – a tough call for a man whose fortune rests on cheap chic manufactured in the murkier corners of the world? He faces it head-on, doesn’t blink. The only thing his VP of communications has suggested is that I don’t ask for his life story “because the risk is, that’s your time gone”.

I decide not to ask about his plush pad in Monaco, a tax haven, either. As Green has told reporters before – not angrily, just firm – he pays tax in Britain. He does not claim non-residency. (However, that Britain’s ninth-richest person has received hefty dividends from Taveta Investments, which is in the name of his Monaco-based wife, Lady Tina, has been widely reported; less publicised is the fact that he has not done so for the past four years.)

In Australia, Green’s best-known brand is Topshop, which, famously, carries a collection by Kate Moss and sells in Incu in Sydney, as well as in New York, Paris, Hong Kong. It also sells in The Department Store in Takapuna, New Zealand, where, when the brand arrived last May, the first sale was at 7.03am and it took four hours to clear the queues around the block.

Green’s Arcadia Group, privately owned by Taveta Investments, also numbers a score of High Street chains not present in Australia, as well as vast and growing e-commerce sites. The brands operate in more than 30 countries across Europe, the Far East and Middle East. Pretax profit for 2008-09, the most recent data available, was £213.6 million, up 13 per cent from £188.9 million. This in a recession still being felt deeply in Britain.

Those MBAs that have become fashion’s favourite accessory are not for this high-school dropout. “There’s parts of it you can learn, which are probably the mechanical pieces,” the billionaire concedes. “But you can’t learn to have a good eye. You either have it or you don’t.” Of course, Green has it and his decisions are snappy. “I’m doing this on the run, I’m turning up, show it to me,” is how he explains his M.O.

“So just now, I was just going through ladies dresses for Christmas; before that, knitwear. When you’ve finished, I’m going to see Kate Moss about her collection. Do I chuck stuff out I think won’t work? Yeah. I saw some knitwear this morning. Didn’t like it on the hanger. Then I’m looking at dresses and I asked [myself]: ‘If this was your last bet, is that where you’d be putting your money?’ In my mind, you weigh up the risk/reward box. I said, ‘If you want to buy a dress that sells at £40, and you want to buy a dress that sells at £70, buy 5,000 of the one that sells at £40, and 600 of the one that sells at £70. It’s not negotiable – unless they prove to me the reason why they think I’m wrong.”

Green hails from London’s Croydon, a suburban sprawl better known as the birthplace of Kate Moss, whose Topshop collections reward her with an undisclosed fee, plus a percentage. As for the ‘Sir’ bit, no one from Croydon, where there are no stately homes or rural acres, has one of those inherited toff titles. Sir Philip Green’s was earned, bestowed for services to business. He was born not rich, not poor. His parents ran garages, electrical shops, property. When he was 12, his father died, his mum carried on and he helped out in the business during school holidays until he left school at 16 and started out on his own. He hawked cheap shoes from China, then jeans. Then he bought up some struggling shops, was making money and, well, let’s fast-forward to 2002, when he acquired the Arcadia Group, including the Topshop chain, for £850 million – or we will, indeed, be here all day. He acquired British Home Stores, rebranded now as Bhs, before Arcadia but has failed in three attempts to grab the High Street prize that is the giant Marks & Spencer.

No surprise that the king of the hill is both liked and loathed; he’s liked by Kate Moss and Naomi Campbell – both of whom call him ‘Uncle Phil’ – and by most key staff, who praise his unerring instinct, photographic memory and ability to helicopter in (often literally) and sort things out. Green is loathed, or more accurately envied, by a certain segment of the British tabloid press, which deems it obscene for a man who has made his own money to relish spending it, hence snide asides about the Gulfstream jet, the pad in Monte Carlo, the family cruises aboard the 63-metre yacht, Lionheart, while the Greens’ now-adult children, Chloe and Brandon, weigh anchor nearby aboard the 33-metre Lionchase.

Sir Philip and Lady Tina throw lavish parties, hiring Beyoncé or Rod Stewart to entertain their guests. The list of charities supported by a spectacularly fat wallet is long, so we’ll start and end with how Green first met Moss when he paid £60,000 for a kiss in a charity auction. Aware how seedy taking the prize would look, he donated it to the underbidder, Jemima Khan. Images of the girl-on-girl smooch went around the world.

You won’t, by the way, find many of the fashion pack scoffing at Green, especially since it was under his ownership that Topshop, once notorious for rip-offs that stole designer ideas, turned into a fulcrum of creativity. For almost a decade, Topshop has been funding New Gen designers in the early stages of their careers, plus (brilliant this) every season, Green and team set up what has to be the world’s most glamorous soup kitchen to feed and water (and champagne) the international fashion pack during London fashion show season.

Green takes plenty of time off – summer on the Med, winter in Barbados, fitness breaks in the US in between – but that isn’t to say he switches off. “I went walking in Arizona last week and a lot of the time I spent thinking, ‘How can we do things differently? How do we adjust to the new world we live in?’” he says. “We’re in an over-shopped world, so you’ve got to create more theatre, more fresh … You’ve got young kids now who spend their time on this Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and every other form of communication on the planet. You have to be clever, smarter, newer …”

Back when Green was flogging his first cheap shoes, the consumer didn’t care about workplace practices, ethical fashion, carbon footprint. Arcadia owns none of the factories in about 60 countries – including China, India, Mauritius, Romania, Turkey – that supply its stores, although, of course, its management and staff are acutely aware that proof of something ghastly, like child labour or mistreatment of women, could threaten everything. Arcadia funds what is probably the global clothing business’s biggest compliance team, last year alone staging 1,044 factory ethics audits, carried out by independent bodies trained not just to look but to ask, and in such a way that those on the economic margins fearful for their livelihoods are able to respond.

“When you’ve got a business directly employing 45,000 people, therefore probably indirectly [benefiting] 150,000 with families and kids, you know everyone is watching,” Green says. “I want to sell the best products I can, at the best price I can, in the best quality I can and there’s no point cutting corners, because you’ll get caught. You’ve got to educate the people who work for us that we want to do things in the right way. We run a very professional, proper ship. There’s no dodging round.” In 2009 alone, the group rejected approaches from 37 new factories until work practices were brought into line. Thus, the consumer can enjoy fast fashion, confident that it has been produced fairly, although there are still improvements to be made. “I don’t want to be a manufacturer,” Green says. “I finance them; I lend them money; I help them buy machinery; I help them build factories but I don’t want to be the owner because I don’t live there. I can’t put my hand on my heart and say to you I know about every single worker. We’re shipping 150 million garments a year. I can’t look you in the eye and say I can guarantee every single piece because someone’s got to go to Timbuktu, make it, inspect it, colour it, ship it. But, hopefully, we are doing as good a job as we can.” Arcadia also has an in-house ‘police’ force, the Fashion Footprint Group, which has a clear mandate to align social responsibilities with business practice, encompassing everything from recycling to taking a stand on the mulesing of Australian sheep. (From the end of 2010, Arcadia will not work with wool suppliers who practice mulesing against fly strike, irrespective of the use of pain relief.)

But enough of the worthy stuff. What Green really wants to talk about is shopping, knowing that, on the way here, I’ve popped into some of the stores. “What didn’t you like?” he demands. Eyes locked, I say I found the flagship Bhs store hard to navigate. “In which way?” The first floor didn’t entice me. “OK, that’s because you walked up [and] so hit childrenswear first. There’s always a struggle and a debate how we tell people what is on each floor. We’ll fix that.” On to Topshop, where the crowds and the chaos and the neon may be heaven on a stick to Sir Philip and every teenager – “if you took 20 CEOs to Topshop, they’d be dishonest if they didn’t say, ‘Wow, this is a real retail experience’,” he beams – but I found it such a jumble and so packed. “Jumbled up in which way?” he booms, “and who complains if it’s busy? Put that on your tape! That’s what those retailers want!”

Of course, what Topshop has, which fast fashion competitors such as Zara and H&M don’t have, is Kate Moss. (H&M did have her, but dumped her after an alleged brush with drugs earned her the nickname ‘Cocaine Kate’ in 2006.) As the myth goes, Kate moseyed up to ‘Uncle Phil’ in a restaurant a couple of weeks after the paid-for pash at the charity do, said something along the lines of, “We’re both from Croydon, let’s do business together”, and it’s been the music of the tills ringing ever since. But it wasn’t quite like that. Negotiations, apparently, were protracted, especially as Green, used to people snapping to attention, needed to be convinced a fashion princess could do things his way. “To be honest with you, at the time, without being conceited, I think it was actually pretty brave because a lot of people had dropped her,” Green recalls now. “People said to me, ‘Are you sure?’ And this is back to instinct, because that told me ‘Good moment’. Topshop had never had a ‘Face Of’ so it was a complete departure. Part of being an entrepreneur is risk and my attitude was, if I’m wrong, what’s the worst that’s going to happen to me? It’s not going to threaten my whole business.”

Actually, it has lifted it hugely. Moss is helping to push the image of Topshop to a whole new level. “It would be fair to say it [lifted] the profile,” Green says. “It’s never been a huge piece of business, and it was never planned to be a huge piece of business. It was about her brand, our brand coming together and you hit the right mood, the right moment. But at the end of the day, the product can’t lie. The merchandise has got to be great. You can’t kid people, and that’s what’s key.”

“Of course, Kate Moss helps,” says designer and retailer Karen Walker, of The Department Store in Auckland. It was Topshop that suggested forging a deal with the hip Kiwis of Takapuna, following successful partnerships with Opening Ceremony in New York, Colette in Paris, Laforet in Japan and Lane Crawford in Hong Kong. Walker says, “The volcano [in Iceland this year that disrupted air travel worldwide] interrupted our initial deliveries, so what we ended up doing was a one-weekend preview, which sold out, then we closed down for two weeks and the second opening was even bigger. We’re the custodians of the brand in New Zealand and both companies, long term, will benefit from the mutual experience.”

The brand made its Australian debut in October 2009 at Incu, transforming a little-used upstairs space above the Paddington store into a must-shop destination. “It’s provided us with a whole new customer base,” Incu director Brian Wu says. “Now, customers can go upstairs to our Topshop area to buy pieces to wear on the weekend and then head downstairs to buy a jacket they have been saving up for, which will last them for many seasons.”

As to why people somehow go more crazy for Topshop than its key competitors, specifically Zara, Green puts it thus: “Zara’s is a great business. I admire and respect it and I’d love to own it. We’re in a slightly different business, though. We’re more edgy. Mr Ortega [Amancio Ortega, Zara’s founder] told me one of his favourite shops in the world is our Oxford Street store, and if you’re in our industry, it would be.”

Later, we’ve moved on to chat about a schools program dedicated to fostering entrepreneurial flair when there’s a sudden ‘knock-knock’ and, “Sir Philip, your 1.30 is here”. It is 1.28pm. “Hello, Naughty,” he calls out through the open door, “with you in a minute.” “Hi Uncle Phil,” Kate Moss says as she pops her head around the door, then he’s back with me, 100 per cent focused, wrapping things up before we shake hands. And then Moss comes in, shakes my hand and we’re done. So it’s a minute later, back in the snazzy reception that the true power of Sir Philip Green hits me. Yeah the billions and the retail turnarounds in record time are impressive, but lordy! What about getting a supermodel to turn up two minutes early! ■