Tag Archives: Diane von Furstenberg

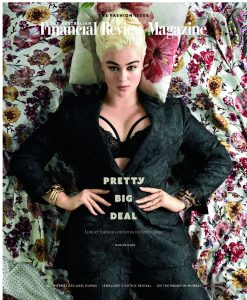

AFR Magazine – It’s A Wrap

It’s a Wrap – Diane von Furstenberg – Australian Financial review

AFR | April 2011

It’s a Wrap

by Marion Hume

Diane von Fürstenberg has started a business, sold a business, started again, been a worldwide fashion phenomenon not once, but twice, appeared on the cover of Newsweek. She has dressed Michelle Obama, advocated for women’s rights, presided over the Council of Fashion Designers of America, married, divorced, married . . . Let’s stop there, because it’s exhausting. But there’s one thing she will never do: design for men.

For von Fürstenberg, who now has her first Australian store at Westfield Sydney, everything comes back to women; being a woman, dressing women, helping to give a voice to women around the world. Which is not – let’s get this clear – to say that Diane von Fürstenberg (often shortened to DvF) has any dislike of men. Or they of her. Before we get into a private – and all signs indicate, highly lucrative – company, a few examples first of female force.

Example 1. A conference, the room airless, the delegates bored. DvF prowls to the podium and, as deeply unPC as this sounds, it is as if the embodiment of sexual energy has taken control of the room. People are mesmerised, twitchy. It is an extraordinary moment.

Example 2. I am interviewing a chief executive at Claridge’s, the top London hotel, to a background of the gentle clatter of porcelain teacups on saucers. DvF enters, the sedate salon goes silent. Everyone – EVERYONE – turns to watch her go by. “She’s like a panther,” swoons my business titan, to the air, not to me, as the ravenhaired beauty in heels passes our table. Did I mention von Fürstenberg is 64 and a grandmother?

“I do use my female power,” she says when, some months later I’m in New York, sitting across the desk from cheekbones that have sunk a thousand ships. It’s the day after her fashion show, which was full of wearable, bright, practical pieces designed by the brand’s creative director, Yvan Mispelaere, a Frenchman who is exChloe, exGucci.

Von Fürstenberg’s role these days is as mentor to the company built in her image. As to that, while she has utterly embraced the can-do American dream, her look is old world, sultry (unBotoxed), alluring. “I have always used my power. I used it when I was tiny as well,” the Belgian-born fashion icon, who speaks four languages fluently, is saying. “We all have that power. I have never met a woman who is not strong. Sometimes they hide it. Sometimes they have a husband, brother, father who puts the lid on them but, then, when it is needed, the strength comes out.”

She was born in Brussels on New Year’s Eve, 1946, to a Moldavian refugee father and a mother who, just 18 months before, had been liberated from a Nazi camp weighing just 22 kilos and who was not expected to live, much less bear a child whom she would raise to face life headon.

Diane, with a mop of brunette curls in an age of blondes, grew up smart, went to Geneva to study economics, met Prince Egon von Fürstenberg, married him, moved to New York as one partner of that era’s ‘it’ couple, had two babies back to back and, from an initial investment of $US30,000, was a tycoon heading up an empire with combined retail sales from clothes, licences, fragrance and cosmetics topping $US60 million before her children started school.

“The minute I knew I was about to be Egon’s wife, I decided to have a career. I wanted to be someone of my own and not just a plain little girl who got married beyond her deserts,” is how she explains all that.

Her idea, a simple jersey dress that wraps around the body and ties over the hip, was not original – American designer Claire McCardell had explored similar sartorial territory in the 1940s. Yet von Fürstenberg’s dresses, manufactured by a friend in Italy in graphic prints and with a clingy, jersey sexiness, plugged straight into the ’70s zeitgeist. Being Princess Diane of Fürstenberg helped.

The legendary editorinchief of US Vogue, Diana Vreeland, was among the first wooed. “I think your clothes are absolutely smashing. I think the fabrics, the prints, the cut are all great. This is what we need,” she wrote on April 9, 1970, as von Fürstenberg herself posed in a signature wrap dress, leaning against a white cube on which she had scrawled, “Feel like a woman. Wear a dress”.

Her marriage collapsed as the business grew and, by 26, she was a single working mother (although she remained close to Egon and was at his side when he died in 2004). By 1976, she was on the cover of Newsweek, in virtually the same wrap dress Michelle Obama would wear on the White House lawns 34 years later. (“That’s what you call staying power!” says von Fürstenberg). By day, wherever she went, women would stop to tell her of turning points in their lives when they were wearing her label. By night, she relished walking alone into legendary nightclub Studio 54 to hang out with Mick and Bianca Jagger, Liza Minnelli, Andy Warhol, Calvin Klein, Yves Saint Laurent and Halston.

Hers was, she recalls in her 1998 autobiography, Diane: A Signature Life, the life of the huntress. “Men had been enjoying casual relationships for centuries. Now women could, including me.” She is said to have made a joke of asking a Rolling Stone editor to guess how many of his cover stars she had seduced. “I always wanted to live a man’s life in a woman’s body,” was her mantra. When it came to business, Newsweek, in a followup article, dubbed her, “The most marketable female in fashion since Coco Chanel”.

Then came that familiar fashion story of boom and bust. After a damaging period of overextension, she sold her company in 1983, travelled, moved to Bali, to Paris, ran a publishing company – this while her royalties, which had been $US4 million, dwindled. The tarnished brand was looking like a ’70s throwback – until that became a good thing in the ’70s revival of the mid-1990s.

American designer Todd Oldham invited von Fürstenberg to a fashion show that he said was a homage to herself. As she wrote in her autobiography, “part of me was flattered and part of me felt like saying, ‘wait a minute, I’m not dead yet’.” Meanwhile her daughter, Tatiana, and her then daughter-in-law, duty-free heiress Alexandra Miller, were both girls in their 20s raiding her vintage pieces to wear.

On a trip to Paris, von Fürstenberg ran into Rose Marie Bravo of Saks Fifth Avenue (who would go on to rejuvenate Burberry), who told her, “Diane, we need your dresses.” In September 1997, the wrap dress was relaunched at Saks and sold out. Today, although it is everywhere, it is a particular blessing in Australia, given it is light, cool, businesslike yet feminine – as long as you have curves and confidence.

Actually, DvF had started her comeback in 1992, on television. She was one of the first to embrace televised home shopping channel QVC, racking up numbers with a range called Silk Assets. She saw the light early on in electronic selling, thanks to her association with Barry Diller who, in 1992, resigned as chairman and CEO of Fox and took a $US25 million stake in the shopping channel (it is now also online). Now chairman of IAC/InterActiveCorp, he and von Fürstenberg married in 2001, the occasion for him to present her with 26 gold wedding bands, one for each year since they’d met. As von Fürstenberg wrote in her biography, “Our relationship was unique from day one and quite unexplainable . . . Later I would have other people in my heart and in my life, but somehow Barry was always there.”

The sixstorey DvF New York flagship store is way downtown, on a wide cobbled street in the Meatpacking District next to the High Line, a tranquil garden along an old elevated rail line. It is in marked contrast to the interior of von Fürstenberg’s office – a riot of hot colour and girls in heels negotiating a six-storey central staircase embedded with Swarovski crystals.

Von Fürstenberg’s own airy office is decorated with photos of family and friends. Her son, Alexander, works in finance; her daughter, Tatiana, is a filmmaker. While grandchildren Antonia, Talita and Tassilo are still young, she talks openly about how she hopes they will one day join the company. This daughter of a Holocaust survivor has always been a philanthropist. Today, ‘giving back’ includes cohosting annual Women in the World summits with highprofile magazine editor Tina Brown. Speakers have included US Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton and Queen Rania of Jordan, while four DvF awards a year, each of $US50,000, go to those who display leadership, strength and courage in fighting for positive change for women everywhere.

“My cause in life is to empower women,” she tells me. “Fashion has led me to this incredible dialogue with women always and … there was always a very real relationship with me and women. Now I am in the fall of my life, part of what I do is to share experience.” She shares the cash too. “When I recreated the wrap dress, I committed that for every one made, $US1 would go to St Jude hospital, a children’s research institute (in Memphis, Tennessee). One dollar doesn’t seem much, but when you do hundreds of thousands, it’s forever.”

As for the lessons of running a global business second time around, she says there is one key difference, one key similarity. Different is her clarity. “I know now you can go nowhere without clarity. What is it you want to do? How? You have to see it; it has to be clear. What kind of product? Once you have clarity, you have strategy, and once you have clarity and strategy, you have success.”

The similarity is a lesson from her mother. “Fear is not an option. Insecurity is a waste of time. The most important relationship you have in life is the one with yourself. In order to have that and to like yourself, you have to be very honest. That’s what I most want to pass on to my grandchildren.”

Africa’s influence in the fashion industry – Financial Times

A long way from the World Cup epicentres of Johannesburg and Durban, catwalkers in New York and Paris are already marching to an African beat. And why not? If global business will have its eye on all things African this month, chiming with the prevailing mood makes economic as well as sartorial sense.

The work of Nigerian-born, London-based Duro Olowu, for instance, combines vintage couture fabrics and silhouettes with African prints (Princess Caroline of Monaco wore an Olowu evening gown at the Bal de la Rose – an annual event in Monaco attended by the royal family – in March). “What’s interesting,” Olowu says, “is the level of sophistication, which reflects the way African people have always combined European fabrics with indigenous culture. For a long time, there was a sense that this was limited to Africa but now it has become global. Combined with an awareness of social responsibility, it makes for a powerful statement.”

Fashion’s big hitters are interested. Diane von Furstenberg has created a “tribal tattoo desert sugar” wrap dress for summer; Dries Van Noten has used Ikat fabrics from Lamu and Zanzibar with abandon; and Alber Elbaz showed fierce feather and bead neckpieces at Lanvin’s autumn/winter 2010 show in March.

But there is more going on here than simple visual pillaging for mood board inspiration. Elbaz’s work, for example, was inspired by a meeting with United Nations officials to discuss potential projects for the brand in sub-Saharan Africa. As for von Furstenberg, back in March she co-hosted the “Women in the World” summit in New York, which included Hillary Clinton, Meryl Streep and female micro-financing collectives from Nigeria to Liberia.

Increasingly, fashion professionals are making efforts to merge authentic African techniques with high fashion. As Olowu says, “Certain techniques, whether it’s block printing or beading, can’t be faked, and using the real thing gives a garment an integrity recognised by designers and consumers alike.”

One well-known Africa-involved ethical brand is Edun. Its new designer Sharon Wauchob has just returned from her first trip to east Africa. She was struck by “the freshness as far as our industry is concerned. We’ve tried other countries like India for so many trends, but here are crafts that have not been explored in terms of [western] fashion.”

Wauchob hints that the collection to be shown in New York next September will include “metal and beads but something beyond ‘Let’s put these Maasai beads on a T-shirt.’” Meanwhile Edun has launched a mini World Cup line, which includes African-produced T-shirts with a football motif. All proceeds will go to the Conservation Cotton Initiative in Uganda.

Stephanie Hogg, founder of Sierra Leone-based NearFar, believes that “it is possible to create sustainable emplyoment through fusing African creativity with western demand for fashion.” NearFar creates printed playsuits and mini-skirts so enticing that they have been snapped up by cult chain Anthropologie.

Holly Hikido, a former Barneys New York fashion buyer, now commutes between Italy and Addis Ababa to collaborate on a line of featherweight scarves labelled “Sammy Made in Ethiopia”. Her former colleague Julie Gilhart, senior vice-president and fashion director of Barneys, says they are “bestsellers” across the US.

Max Osterweis, who along with ex-Gap designer Erin Beatty runs New York-based, Kenyan-made Suno, agrees. “The idea with Suno is to make clothing covetable enough internationally to provide our tailors in Kenya with long-term employment,” he says.

Michelle Obama is a customer and Carol Lim, of New York’s Opening Ceremony store, is also a fan. “I love Suno because of how the bright colours make me feel,” she says. “It’s kind of like an energy boost.” When customers hear the brand’s made-in-Nairobi story, “it makes the purchase all the more meaningful”, she says.

Helping connect such projects with bigger brands is the Ethical Fashion Programme of the ITC (The International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the World Trade Organisation and the United Nations). Run by Simone Cipriani, a veteran of the Italian fashion world, the programme aims to provide long-term employment under certified fair labour processes for artisans working in impoverished areas.

While the catwalk names getting involved remain under wraps, there are already repeat customers, such as Luisa Laudi, creative director of MAX&Co, a brand of the Max Mara Group aimed at younger customers. “Working with Kenyan craftswomen in the slums is complicated and not like producing accessories in Italy,” she says, “but this is not charity. The accessories are great and in line with our production standards.”

But, Cipriani warns: “If fashion companies don’t fulfil their promises, the damage is severe. There are cases of micro-producers abandoning their own cottage industries to work with outsiders and then it stops and they are also deprived of the little they had before. The result is brutal. They starve.”

The ITC’s long-term projects are designed to mitigate against the damage of Africa going in and then out of fashion. Olowu says: “The world, including the fashion world, is becoming ever-more global. I think the African influence is more than a trend. Now it’s part of the melting pot.”