Tag Archives: Edun

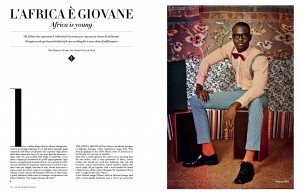

Fashion Hearts Kenya? – The Business of Fashion

How has the recent terror attack on Westgate Mall in Nairobi changed things for designers with manufacturing connections in Kenya? Marion Hume reports.

Business of Fashion | October 2013

NAIROBI, Kenya — Bex Manners, aka Bex Rox — which is the name of her costume jewellery line — figured it would be sensible to sit down for a proper brunch. A long working day lay ahead, then the midnight flight back to London. But time was pressed. So instead she grabbed take-out from ArtCaffe and went on her way. Less than 15 minutes later, terrorists stormed the Westgate Mall. The four-day siege in Nairobi left at least 67 dead, 39 still missing, a nation reeling.

You might be surprised who in the fashion world has ties to Kenya. Bex Rox is known for rock and roll, party-all-night-in-Ibiza edginess, not “ethical” or “Africa.” A connection to the continent happened by chance. She was in London’s Portobello Road, bumped into Cristina Cisilino (of the high-end jewellery producer, Crea Africa, based in Nairobi) “and the next thing I knew, I had a 40-piece collection being prototyped and I flew out to [Kenya] to see samples through the final stages.”

A Paris fashion week party to show off “Afrika” — including bold bracelets in gold-plated brass and knuckleduster rings in sock-it-to-you brights — went ahead as planned. Yet as guests sipped cocktails and took in the view of the Eiffel Tower from the private residence, on loan for the night, talk turned to near-misses. “The first thought was, ‘Are our friends safe?’” said Erin Beatty, design director of Suno and veteran of the New York-to-Nairobi commute. “Common sense told all of us not to go to Westgate,” said a subdued Max Osterweis, founder of Suno, the label named after his mother, who has had a home on the Kenyan island of Lamu since his childhood. “But when you need something for your laptop, it’s where the Apple store is. It’s where the book store is; the ATM.”So what now?

Does fashion “heart” Kenya?

Does fashion care?

“I can say our customers have been buying a lot,” says a still-shaken Manners. “Is that because of what just happened? Honestly, no. It’s because it’s handmade, lovely and I can cater exclusively for small quantities; I can offer an amazing colour palate with the Maasai beading.”

Osterweis is of the opinion that caring can never come first in fashion, this despite founding Suno because he cared so much. The son of a wealthy family, he launched Suno instead of writing a bit fat charity cheque after Kenya’s post-election violence, in 2008, claimed over a thousand lives and left 350,000 people displaced. As he told me when we met in Nairobi for a Time magazine story (April 2009), “I wanted to set an example to show that investment in Africa need not be about building more safari lodges.” An entirely “made in Africa” label was never the ambition however. “I’d seen brands being unrealistic, so we’ve invested in people’s strengths, produced what we knew could be done well in Kenya, while also producing elsewhere,” he told me then, revealing his aim to dress cool girls for hot, New York-summer nights, while, at the same time, providing work to skilled Kenyan artisans (as well as those in Italy and the United States).

Today, fans of Suno include the actress Elle Fanning, the artist Cindy Sherman and American First Lady, Michelle Obama. And as the label has soared, so too have the number of units made in Osterweis’ second home nation, bolstered by an additional online offering of sneakers, pyjamas and totes made exclusively in Kenya. “No one has said ‘I’ll order more,’” he says now. “People buy what they like.” As for his commute, “Nothing changes, except we won’t be eating pizza at Artcaffe. What happened is not a Kenyan problem, it’s a global problem. It’s not life as usual. It’s dealing with life as it is.”

Because it was founded by Bono and his wife Ali Hewson, Edun attracted first ludicrous expectations then harsh criticism, especially after pragmatic, LVMH-appointed CEO Janice Sullivan insisted on scaling African production back to ensure a viable economic foundation for the brand. (“Out of Africa, Into Asia” was how The Wall Street Journal reported the decision, back in 2010). Sullivan’s tactic to pull back, shore up, then reintroduce the African production that was Edun’s central “raison d’etre” seems to be working at last. Over 80 percent of the line is now made on the African continent, although the percentage in Kenya, where it all began, remains quite small.

“No one has brought up Kenya once,” says Sullivan at Edun’s Paris showroom, this while fingering a goat horn and silver collar, made in collaboration with Nairobi-based jeweller, Penny Winter. Instead, she says, the chatter is about the brand’s new designer, Daniela Sherman (formerly of Alexander Wang and The Row). So will Edun stick with Kenya, especially given growing production in Madagascar means the brand could easily pull out of a trouble spot and still hit its “made in Africa” targets? Ali Hewson, who has joined us, looks incredulous at the suggestion. “We were in Kenya for the riots of 2008. We were in Uganda for the attack at the World Cup. We were in Mali two weeks before the coup. We’re Irish!” by which she means proximity to risk won’t change a thing.

Ilari Venturini Fendi admits to being nervous in Nairobi, “constantly aware of the possibility that something so bad might happen. It’s always been quite complicated to work in Kenya.” Whether she returns soon or not, there’s no question that her socially conscious, made in Africa accessories brand, Carmina Campus, will continue to operate in the country, where the facility to achieve the label’s ethical goals at the high quality expected by a Fendi is already established. Each season, artisans in Italy connect with those living in the slums of Korogocho and Kibera via video which, Venturini insists, is not about “us” teaching “them,” but instead an exchange of ideas and know-how.

Chan Luu’s seed bead wrap bracelets in raw-cut leather are hot sellers. Do global stores care that the Los Angeles-based celebrity jeweller produces in Kenya (where she may be the largest single contractor of Maasai beaders, all paid a fair wage)? “What matters is everyone buys!” she shouts across the melee of those placing wholesale orders at a showroom in Paris. In a quieter moment, she adds, “I believe poverty can create violence. My customers want to do good for the world, so they support these ethical fashion projects.”

Both Luu and Venturini Fendi were introduced to Kenya via The United Nations’ ITC Ethical Fashion Initiative, (full disclosure: it was on assignment in Kenya for Time that I met the head of the initiative, Simone Cipriani, and, as a result, began working with them). “The terrorist attack has produced a double effect,” Cipriani says. “Yes, short-term travel plans of colleagues in the fashion industry have been disrupted. First of all, we work to keep collaborations with us stable, supplying African artisans with ongoing work in a meaningful way. Another important reaction is from fashion brands wanting to bring work to Kenya (several more brands have reached out since the Westgate siege). Terrorism is a global threat. A way to fight is by giving work and dignity to every human being. And if we do it, by creating beautiful, unique and gorgeous products, so much the better for everybody.”

Surely eternal activist and ethical pioneer, Vivienne Westwood would agree? Did she include so many Kenyan bags in her Paris show this season out of solidarity with artisans she met when she visited Nairobi in 2011? “They’re my favourite bags, that’s why I show them,” says ever-honest Dame Viv backstage. “I show them because they’re lovely.”

Another Edun- Janice Sullivan – AFR Magazine

AFR Magazine | April 2011

Another Edun

by Marion Hume

As if the fashion business is not tough enough, Janice Sullivan must also meet Bono and Ali Hewson’s lofty aims for a niche eco label they founded to help lift Africa out of poverty.

There are times when I’m sitting with a Chief executive, who is completely ‘on message’, brilliant at expressing the ‘pillars’ of the brand and at talking through an impressive bottom line, yet I’m thinking, “Yes, but you could be selling paint.” There are other times – rarer these – when I meet a CEO who is perhaps more tentative at first, yet utterly equipped for the unique challenges of the fashion business. A latter case is Janice Sullivan. As she puts it herself, “I come from the back room. I’m hands on. I am all about product.”

Sullivan, an immaculate New York honey blonde in her mid 40s, does not have an expensive MBA. Instead, she has a roll-up-your-sleeves understanding of the logistics of making clothes and accessories in any part of the world. She knows her fabrics; she can tell at a glance how many you can cut of this and how long it is going to take to add beading.

“I started out in production; [was] then in product development; then in merchandising, then took over sales,” says Sullivan, who grew up on the Jersey shore looking across to Manhattan and whose career in New York City, until 18 months ago, involved switching back and forth between Calvin Klein and Donna Karan as she climbed the ladder at two iconic America brands. She was president of Calvin Klein Jeans when Mark Weber, who helms the LVMH business in the US, (which these days includes Donna Karan), asked her to take on a considerable challenge. She is now the CEO of Edun.

In contrast to her past employers, Edun is a minnow; a niche eco brand where the numbers for an item might be 200, rather than 20,000, even 200,000 at Calvin Klein. Since 2009, this eco brand has been 49% owned by the luxury giant LVMH. You will certainly have heard of the pair who founded it in 2005, given they are rock star Bono and his wife, Ali Hewson.

To begin with, Edun received spectacular press, way more than the usual start-up because the world’s media was keen to get up close with Mr. & Mrs. Hewson. Edun garnered renown as the go-to made in Africa label (this even though the majority of product was sourced in Turkey, India, Peru). The mission became the message; that the 53 nations of Africa have way too small a share of the world’s trade (just 3% for 2010) and that producing in that vast continent went at least some way to levelling that inequity.

Ali Hewson, a political science graduate, proved every bit as forceful as her husband at delivering facts and figures about poverty, the numbers of people in sub-Saharan nations decimated by HIV/AIDS and how buying clothes could help. The brand’s mantra, “We carry the story of the people who make our clothes around with us,” was compelling. But while the fashion business worships at the altar of celebrity if that is going to shift stuff, it is neither charitable nor forgiving. Late deliveries, inconsistent quality and lacklustre clothing lead retailers, initially so enthusiastic, to drop the line. It has been reported that the Hewsons pumped US$20 million of their own cash into Edun to keep it afloat while they shopped for an expert partner. LVMH acquired its stake for US$7.8 million.

While the timing was great for Edun, it was also good for LVMH, whose arch rival, PPR/Gucci Group, includes Stella McCartney, a brand that has moved from being perceived as, “the awkward [run] one, by [an] animal rights activist who won’t use fish glue, let alone leather”, to a sustainable, ethical, luxury brand that chimes precisely with the zeitgeist. LVMH needed an eco brand and to get one that could promise rockstar power to the front row (just as the daughter of Paul McCartney can) cannot but have added to the appeal.

The acquisition seemed the signal good times ahead. Sullivan was appointed to steer the brand; Sharon Wauchob, an Irish designer based in Paris, was hired to create a laid-back, modern fashion signature. (As to Wauchob’s nationality, she made clear on the first time we spoke that, “Not everyone Irish knows Bono”. She got the gig based on her achievements, having never before met the Hewsons). LVMH brought business expertise: the ability to help a small company with IT, customs clearance and such like.

Then Bono and Ali Hewson followed the likes of Catherine Deneuve, Keith Richards and Mikhail Gorbachev by appearing in a “Core Values” Louis Vuitton advertising campaign, which also name-checked Edun. Invites went out to a glamourous party to fete the collaboration and to showcase a Louis Vuitton “Keepall” bag, featuring a slick cow horn charm, made by an Edun supplier in the slums of Nairobi. Profits from the bag, as well as the Hewsons’ fees, went to African causes.

Yet not for nothing is there an old saying, “The road to hell is paved with good intentions”. Last September, The Wall Street Journal came out with a damning article headlined “Out of Africa, Into Asia”, containing the revelation that, since joining with LVMH, most of Edun’s clothes are made not by the poor of Africa but in highly mechanised factories in China. The story went round the world.

The WSJ piece was fair (the online version has a few clarifications, but no significant corrections), yet the ramifications of it have been unfortunate. While I was working on this piece, a leading style journalist mentioned she was working on a piece about producing in Africa but “not featuring Edun; they make everything in China.” (To clarify further on the goods that are made in China, this is no longer synonymous with sweatshops; LVMH has stringent codes of compliance for its factory partners).

There were further reasons the WSJ story, its contents cherry picked and reprinted by global tabloids, garnered such traction. Some of this was due to Bono bashing, given he is a divisive figure. Some of it was due to a rare chink in the otherwise impregnable armour of the mighty LVMH (which is rarely criticised and also spends enormous amounts of money in the media advertising its brands).

“I think it is unfortunate some people put a lock on the brand,” says Janice Sullivan carefully. However she then acknowledges, “because of all the press, because of Bono, there was a high level of expectation to not only have a beautiful collection, but to tick all these boxes in terms of sustainability, in terms of where things are made.

“But I think to go forward, you take it carefully and make sure you deliver. You want to make sure you have controlled growth. Our commitment is to make sure we grow the percentage of our line that we produce out of Africa. But it will never be everything.”

Depending how you cut it, 41% of Edun’s production is currently Africa, however this includes the Edun Live line of blank T-shirts, which are bulk-purchased by bands and brands as tour merchandise and are separate from the fashion offer. Also wrapped into that African percentage are items made in Morocco and Tunisia- North African nations that, (Tunisia’s current political turmoil not withstanding), are industrial suppliers to legions of fashion companies.

On the plus side and perhaps galvanised by press scrutiny, Edun has pledged that its fashion sourcing in the poverty belt of sub-Saharan Africa will rise to over 60% by 2013. The highly visible fashion portion which started out as 15% of the collection, is expected to expand to 40%, and with steady attention, each collection should benefit from the transfer of skills needed to achieve these goals. Already, new collaborations are being forged; with The Crochet Sisters, a sisterhood of nuns and young girls, many of them refugees from Zimbabwe, who live and work in a safe environment in Nairobi; with a small company in Cameroon making sneakers and ongoing, with MADE, the Nairobi accessory company that provided the charm on the Vuitton Keepall bag.

Janice Sullivan is a realist. “This is made in Asia,” she says, fingering a fluid silk dress that wraps and ties over the body. “The fabrics are most likely Asian. These are African” she says, pointing to beads of recycled copper adorning a handknit. “I think Edun can be the next big brand but in a different type of way. But right now, it’s about getting it right so we can grow.” Desirability and reliability have to come before any mission.“You can have a great story, but your product has to deliver, it has to be desired by people, it has to be right and on time. And you have to do it over and over again.”

Those who frame Edun’s sourcing of the majority of its offer outside of Africa as some kind of ongoing failure lack an understanding of the logistics that Sullivan is talking about or of the challenges of producing in the sub-Saharan region, home to some of the most disadvantaged people on earth. “As we grow more confident, we will expand our capacity in Africa,” Sullivan says. “But I don’t want to overburden, overwhelm. I want to make sure we concentrate on good, strong pieces we know we can execute, and get them done.”

“Overburden” “Overwhelm” are well chosen words. The challenges of producing in the developing world are legion. I know of this because I serve as a consultant to the UN agency, the International Trade Centre, on its global Ethical Fashion Programme, which encourages top designers to consider marginalized community producers among their suppliers. (Edun is not currently involved with the programme).

As you can imagine, it is not easy to produce high fashion in a Kenyan slum where the population density is 23 times that of Manhattan; neither is it so in war-torn rural Uganda where there are almost two million ‘Internally Displaced Persons’, refugees in their own land because of 20 years of civil war. Add to these, such externalities as lack of a reliable power supply and the need to get workers, especially women, home before dark, (which mitigating against the possibility of overtime).

It is surprisingly expensive to source among the poor. Just one equation; in Laos, one of the poorest countries in Asia, water and education are provided free by the communist regime, meaning the living wage is $3 a day. In Kenya, slum dwellers must pay even for access to drinking water, meaning their living wage is $4 a day – that extra dollar at source significantly upping the end price of a product. Currently Edun sources in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Madagascar and the West African nation of Cameroon.

But one would safely assume that an ethical brand like Edun would be 100% organic, wherever it was producing, right? Wrong. Pesticides kill some 20,000 cotton growers a year from accidental poisoning, while a further million suffer ill health, according to Pesticide Action Network. This is compounded by the devastating effect on the environment. Edun has a noble commitment to organic cotton and has been a key force in the establishment of The Conservation Cotton Initiative (CCI) which enables displaced farmers in Northern Uganda to get the tools and funding they need to return to their land.

Appearance fees donated by Bono and Ali Hewson in the Annie Leibovitz-shot Core Values campaign were donated to CCI facilitating the hiring of TechnoServe, a specialist in rural enterprise, The result has been that the number of farmers being helped has risen from 800 to 3,500, (the target is 8000). Last season, Edun purchased 15 tonnes of this cotton, enough to make some 10,000 T shirts. “We use organic materials whenever possible,” Sullivan said last year, “but it’s not easy”.

Things just got harder- 2011 is an election year in Uganda and President Museveni is distributing free pesticides to farmers. “We’ve decided to push a people agenda rather than the organic agenda,” says a sanguine Sullivan now. “We’ve switched our efforts to teach responsible farming and how pesticides can be used sparingly. Yet she remains upbeat. “These are the kind of complications Edun is willing to embrace in order to thrive and grow. Inconveniences are not insurmountable. They require patience but that pays off if the result is something special.”

Sullivan, a working mother of 15 year old twins, who is also stepmom to her husband’s 15 year old son, says she was ready for a new kind of fashion challenge. She is glad Edun is about forging long relationships around the world. But for Edun to fly, the clothes have to be great. While designer Wauchob has made as many visits to East Africa as she has been able (she has a young baby), she has resisted offering African styles or prints, choosing instead to use her time there researching what it is possible to make.

Hence black crochet skirts, little fringed vests, which are bang “on trend” while the offer sourced elsewhere includes utilitarian parkas (wise, given winters seem to be getting harsher in the Northern Hemisphere fashion cities), snug chunky knits, floaty-long woven skirts and reconstructed Fair Isle patterns in rich earth tones. In other words, clothes that are not chasing youth but can be worn by grown up women such as Hewson, whose style signature is “great pants, layers and a good jacket” and Sullivan, who needs to look like she means business, but not to look “corporate”.

Sullivan is quick to praise the founders. “A lot of great ideas come from those outside the industry…What appealed to me [when I joined] was the idea that we’re all in one world now, and you can’t remove yourself from the process any more. Fashion is a big influencer. I’ve worked for some very big brands. This is still a small brand but I think it has a lot of power.”

Certainly, there is no way Edun could have come so far, so fast without the Hewsons, who remain very much involved. “I’m incredible impressed with how extensively they had already made in-roads, particularly in Uganda. It made my job a lot easier stepping in,” says Sullivan.

Star power continues to create magic. While last season, Sullivan apparently had to reign in Bono’s ambitions for a fashion extravaganza, telling him, “We are having a fashion show. Show is the second word. Fashion is the first word.” This season, he’s helped to lift menswear sales by wearing Edun, as has fellow band member The Edge, during U2’s South African tour. As for womenswear, REM’s Michael Stipe, Hugh Jackman, Helena Christensen and Christy Turlington sat in the front row at the New York show in February.

But neither a sprinkling of stardust or a good heart is enough in the tough business of fashion. “It’s got to be great. No one cuts you slack. I can’t put out something that looks half way, there’s no such thing as ‘we’re almost there’,” says Sullivan. “It’s always about what I can show you now that’s great.” She pauses. “Take those black skirts made by the Crochet Sisters. We’ll do 600 of the skirts, 400 of the fringed vests. No, make that 2,000 units, I’m sure we’ll do that.”

And with just 2000 units – not 20,000, not 200,000 – a community of women, many of whom have fled the violence of war to find unlikely sanctuary on the edge of one of the most dangerous slums in the world can work, eat and stay safe until next season’s order arrives.

Africa’s influence in the fashion industry – Financial Times

A long way from the World Cup epicentres of Johannesburg and Durban, catwalkers in New York and Paris are already marching to an African beat. And why not? If global business will have its eye on all things African this month, chiming with the prevailing mood makes economic as well as sartorial sense.

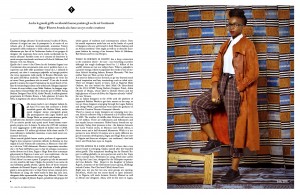

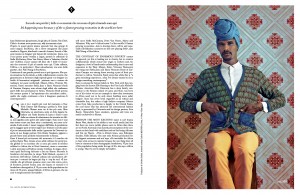

The work of Nigerian-born, London-based Duro Olowu, for instance, combines vintage couture fabrics and silhouettes with African prints (Princess Caroline of Monaco wore an Olowu evening gown at the Bal de la Rose – an annual event in Monaco attended by the royal family – in March). “What’s interesting,” Olowu says, “is the level of sophistication, which reflects the way African people have always combined European fabrics with indigenous culture. For a long time, there was a sense that this was limited to Africa but now it has become global. Combined with an awareness of social responsibility, it makes for a powerful statement.”

Fashion’s big hitters are interested. Diane von Furstenberg has created a “tribal tattoo desert sugar” wrap dress for summer; Dries Van Noten has used Ikat fabrics from Lamu and Zanzibar with abandon; and Alber Elbaz showed fierce feather and bead neckpieces at Lanvin’s autumn/winter 2010 show in March.

But there is more going on here than simple visual pillaging for mood board inspiration. Elbaz’s work, for example, was inspired by a meeting with United Nations officials to discuss potential projects for the brand in sub-Saharan Africa. As for von Furstenberg, back in March she co-hosted the “Women in the World” summit in New York, which included Hillary Clinton, Meryl Streep and female micro-financing collectives from Nigeria to Liberia.

Increasingly, fashion professionals are making efforts to merge authentic African techniques with high fashion. As Olowu says, “Certain techniques, whether it’s block printing or beading, can’t be faked, and using the real thing gives a garment an integrity recognised by designers and consumers alike.”

One well-known Africa-involved ethical brand is Edun. Its new designer Sharon Wauchob has just returned from her first trip to east Africa. She was struck by “the freshness as far as our industry is concerned. We’ve tried other countries like India for so many trends, but here are crafts that have not been explored in terms of [western] fashion.”

Wauchob hints that the collection to be shown in New York next September will include “metal and beads but something beyond ‘Let’s put these Maasai beads on a T-shirt.’” Meanwhile Edun has launched a mini World Cup line, which includes African-produced T-shirts with a football motif. All proceeds will go to the Conservation Cotton Initiative in Uganda.

Stephanie Hogg, founder of Sierra Leone-based NearFar, believes that “it is possible to create sustainable emplyoment through fusing African creativity with western demand for fashion.” NearFar creates printed playsuits and mini-skirts so enticing that they have been snapped up by cult chain Anthropologie.

Holly Hikido, a former Barneys New York fashion buyer, now commutes between Italy and Addis Ababa to collaborate on a line of featherweight scarves labelled “Sammy Made in Ethiopia”. Her former colleague Julie Gilhart, senior vice-president and fashion director of Barneys, says they are “bestsellers” across the US.

Max Osterweis, who along with ex-Gap designer Erin Beatty runs New York-based, Kenyan-made Suno, agrees. “The idea with Suno is to make clothing covetable enough internationally to provide our tailors in Kenya with long-term employment,” he says.

Michelle Obama is a customer and Carol Lim, of New York’s Opening Ceremony store, is also a fan. “I love Suno because of how the bright colours make me feel,” she says. “It’s kind of like an energy boost.” When customers hear the brand’s made-in-Nairobi story, “it makes the purchase all the more meaningful”, she says.

Helping connect such projects with bigger brands is the Ethical Fashion Programme of the ITC (The International Trade Centre, a joint agency of the World Trade Organisation and the United Nations). Run by Simone Cipriani, a veteran of the Italian fashion world, the programme aims to provide long-term employment under certified fair labour processes for artisans working in impoverished areas.

While the catwalk names getting involved remain under wraps, there are already repeat customers, such as Luisa Laudi, creative director of MAX&Co, a brand of the Max Mara Group aimed at younger customers. “Working with Kenyan craftswomen in the slums is complicated and not like producing accessories in Italy,” she says, “but this is not charity. The accessories are great and in line with our production standards.”

But, Cipriani warns: “If fashion companies don’t fulfil their promises, the damage is severe. There are cases of micro-producers abandoning their own cottage industries to work with outsiders and then it stops and they are also deprived of the little they had before. The result is brutal. They starve.”

The ITC’s long-term projects are designed to mitigate against the damage of Africa going in and then out of fashion. Olowu says: “The world, including the fashion world, is becoming ever-more global. I think the African influence is more than a trend. Now it’s part of the melting pot.”