The Bees Knees

AFR | December 2011

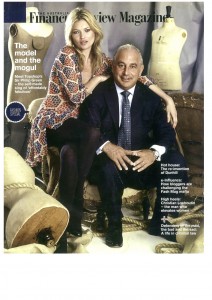

by Marion Hume

Cor blimey, I should have turned up in a “Pearly Queen” outfit, because I seem to have walked in to Old London Town. Fish and chips? Served in twists of newspaper by waiters in bowler hats. A nip of gin? Coming right up. Red-jacketed Queen’s guards? Yes, but unlike those standing sentry outside Buckingham Palace, these lads are sporting Extra Wow Lash mascara under their towering bearskins.

The venue is an iconic London landmark, the Battersea Power Station that is truthfully too far from the steeple of Bow Bells for anyone to claim to be cockney. But that’s not going to stop supermodel “mockney” Kate Moss from arriving in style. Pump up London Calling by The Clash and look! That’s Kate’s chopper overhead! It touches down and the ultimate London girl then runs down a red carpet in a little red dress to match her Lasting Finish shade #1 red lips.

That certainly gets the party started to celebrate her 10-year association with Rimmel London, (which used to be called just plain ‘Rimmel’ and was actually founded by a Frenchman). This birthday bash has been going on all day. Earlier, it was red, white and blue cupcakes and an English tea party at Claridge’s hotel, where fashion’s famous sphinx, (again sporting Lasting Finish shade #1) picked up a microphone and actually spoke, albeit briefly.

Interviewer: “What was it like filming the latest commercial?”

Kate: “It was so much fun.”

Interviewer: “What was the best bit?”

Kate: “The last shot was good, thank you for coming everyone.”

Come they have. The beauty press have been flown in from all corners of the globe to try New Lasting Finish 25 Hour Foundation and Vinyl Max Gloss. Me? While I admit I’ve grabbed a Scandaleyes mascara and Traffic Stopping eyeshadow in Over the Limit #001, I’m here to talk to the boss, Bernd Beetz, (and yes, it does sound like Burned Bees).

Beetz helms Coty Inc. (which has Rimmel London along with Calvin Klein fragrance and Sally Hansen nail varnish and Lancaster skincare and JOOP! body splash, etcetera, etcetera, in a vast portfolio). While Moss’s 10 years with Rimmel have seen her jumping off double decker buses and roaring past Big Ben on a motorbike and going from “nought to Sexy in seconds”, Beetz has been the puppeteer, dramatically repositioning a ragtag of mass-market fragrances and toiletries as well as marshaling new launches and snapping up acquisitions to create a global beauty behemoth with revenues of more than $3.5 billion in 2010. A word on those acquisitions. In just two months this year, Coty snapped up four major beauty companies, Dr. Scheller Cosmetics, Philosophy inc, The nail line, OPI and TJoy, the latter a Chinese skincare brand.

Australia has a role to play in all this. Talking just Rimmel alone, we rank fourth among key markets and are also viewed as a territory with the maximum upswing (which translates as “they could sell even more here and they’re certainly going to try”). Already successful is Rimmel’s value priced (cheap), self-serve (grab your own,) accessible (teenage), make-up, although even after HRH’s recent, well received visit to Queensland and beyond, you wouldn’t be betting on how many Union Jack eyeshadows in Royal Blue and Purple Reign will be sold on these shores.

By now Bernd Beetz (61 year old, wearing a suit, no tie he commutes between Coty’s Paris and New York HGs and is almost always in transit), is posing for the paps with Kate Moss and his close lieutenant Steve Mormoris, the Senior Vice-President, Global Marketing for Coty Beauty. Coty has two main divisions; Coty Prestige, which encompasses perfume and cosmetics for such brands as Karl Lagerfeld, Marc Jacobs, Vivienne Westwood and Balenciaga; and the somewhat more “masstige”Coty Beauty, with labels such as Kylie Minogue, Beyonce Knowles, David and Victoria Beckham and Kate Moss, also has a Coty perfume range that sells in supermarkets.

Moss has good reason to be hugging Beetz and Mormoris, considering these businessmen stuck by her when she was mired in an alleged cocaine scandal that saw much edgier fashion brands judge her too hot to handle. While Mormoris decided not to ditch her, ultimate veto lay with Beetz. That he did not let Moss go is among a series of sometimes surprising decisions that made him the subject of a Harvard Business School paper; Bernd Beetz: Creating the New Coty by Professor Geoffrey Jones and Senior Researcher David Kiron.

“Is this an average day for you?” I ask Beetz, (and given the scene, what would you have tried as an opening gambit?) Beetz is German. He considers the question and replies with care. “It is not so average. After this, I go on to…normal business. This event is particular because it marks the 10 year anniversary of me taking over Coty. It is 10 years since working here with Steve and I took Kate Moss as the key spokesperson for Rimmel, which was my first big decision.”

And you’ve stuck with her. “Basically there were two things. She was loyal to us, so we were loyal to her. We are not people that dump a loyal supporter and we were also lucky because we are a private company. So even if our business would have gone down, it is something we could have afforded. Secondly, everything is not sugar-coated and straight-forward in life, so it seemed not be a bad idea to stick with her and show that life has difficulties. I think that in hindsight, it was a good idea.”Other businessmen might agree, especially if it were to lead to them partying with one of the most famous beauties on earth in the roped-off VIP area.

Bernd Beetz comes from Heidelberg, was educated in Mannheim and is the son of an engineer who built power plants. He speaks English, French, Italian and Turkish fluently (“with conversational Spanish”). For 20 years, he worked across Europe for P&G ( the leading consumer product company, Procter & Gamble), then at LVMH, where he was president and CEO of Dior and is credited with the blockbuster success of J’Adore fragrance.

Securing the top job at Coty was not an inviting prospect in 2001. While the name dates back to 1904 and Francois Coty, a French perfumer who was much admired by Coco Chanel, Coty had been sold and amalgamated and downgraded to little more than a tattered umbrella over a bunch of brands with competing agendas and unimpressive market share. By 2001, Coty had been spun off from a chemicals conglomerate called Benckiser, privately-owned by the Reimann family and run by Peter Harf. However, Harf did have to wisdom to realise that success flogging household cleaning products did not give him the skill set required to build an upscale beauty portfolio on the side. For that, he had Beetz in his sights.

Back then, Beetz was the man-of-the-moment. He had doubled profits in two and a half years at Dior and earned a reputation as an inspired marketer. He was living in a luxury Paris apartment (complete with personal chef and chauffeur). Looking back now, he recalls the experience of working for LVMH boss Bernard Arnault as transforming, citing the luxury goods titan’s mastery at translating concepts into products “He taught me a new aspect on how to approach a luxury brand”. Beetz was surprised to find his old business acquaintance Peter Harf standing in the street outside his door one morning in 2001. Harf approached with an offer he could not refuse. If, after two years, he couldn’t fix Coty, he would be free to go with a big fat bonus. If he could, the company would be his to run as he liked.

Beetz said yes and by the way, he would make Coty one of the world’s top beauty companies within a decade as well. (At the time, Coty ranked 32nd). Today? It’s number 12 according to Women’s Wear Daily’s Top 100 Beauty listing after Kao Group, Johnson & Johnson, Chanel, and LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton. Coty now comprises more than 40 well-known brands available in over 90 markets worldwide.

Beetz has achieved the turnaround first pulling everyone into line and then setting them free. (The Harvard study dubbed this a “Faster, Further, Freer” corporate culture). But setting people free surely carries risk that they are free to fail? “It’s not luck,” is Beetz reply on that. “We didn’t have a major failure. I’m not afraid to admit that we have been by and large very successful.” Part of that success has been wise acquisitions. An US$800 million acquisition of Unilever’s fragrance division, including the Calvin Klein fragrance license along with the romantic scents of Vera Wang and the fashion-forward Chloe made Coty the world’s largest fragrance company. But what of deals that got away? “I know but I’m not going to answer,” says Beetz.

Elsewhere in the beauty business where both the profits – and the losses – are potentially enormous – (for example, 90% of new perfume launches fail within a year) , it is not unusual for big decisions to be made by consensus. Senior executives might be polled on what a teenage fragrance should smell like (mostly just like an earlier success), how the bottle should be shaped (like one that exists) – in other words, companies can be hampered by highly accomplished staffers being part of decisions that have little to do with what they are good at. One of Beetz’ skills has been to let the people best placed to make creative decisions do so. In this, it helps that the company is private. “I don’t think we could have accomplished what we did in the last ten years without the strong support of the family of the mother company,” Beetz says.

“Actually we have the best of both worlds. We have the support of the family which is part of the 7th generation. But they are not involved in the management so we have a clear meritocracy. This entitled me to the job and I have been successful ever since. Nobody in the family works here, not even on the board.”

There are 3 key product pillars of Coty inc:- There’s colour cosmetics, anchored by the storming success of Rimmel, which legitimately earned its “London” tag in 1834 after Eugene Rimmel set up shop away from his native France, then his British-born sons developed the first non toxic mascara. But Rimmel was barely known outside of Britain ten years ago. The strategy since then has been to invest in R&D, to align the brand closely with the vibrant street style of urban tribes, to pump up the image while pushing down the price (its lipsticks sell for as much as 20% less than close competitors).

Next come the sun and skincare lines, which range from Lancaster, which traces its heritage to the jet-set of 1950s Monte Carlo, to TJoy. This has provided a foothold into China through TJoy’s existing distribution channels as well as a platform for expansion. But there’s a challenge inherent here.

Coty’s biggest product category by far, (62% of total revenues) is fragrance. In much of Asia, dabbing on perfume is neither a tradition nor is it popular. Give it time; for Asian markets, Coty now create “flankers”, softer versions of star scents, hence Calvin Klein Euphoria becomes the lighter, entry-level Calvin Klein Euphoria Blossom. Cracking China is the goal of many western beauty conglomerates and here, Coty is far from the front runner. “We are the challenger in that game and we only have a very low presence,” concedes Beetz. “We started off in Europe and then we conquered America and we were a bit behind in China. We acquired TJoy to develop a meaningful presence.” With a bridge to Beijing, will Rimmel be roaring into town? How well is Kate Moss known in China? “She’s known,” says Beetz gnomically.

At the turn of the millennium, you might have described Jennifer Lopez more as notorious; given her relationship with rap mogul, Sean “P Diddy/Puff Daddy” Combs and an incident involving a gun in a New York nightclub. So although J.Lo’s “people” were shopping around the notion that the Latina bombshell might front a fragrance, not surprisingly, there were not a lot of takers. In any case, the category was moribund.

In the 1990s, Elizabeth Taylor had become almost as well known for the fragrance White Diamonds as her role as Cleopatra but, with her notable exception, over the next decade, celebrity scent had diminished to dime store sales for cable TV stars.

Yet against this backdrop, Beetz’ gut told him a celebrity scent was exactly what was needed to power out his re-energised Coty. He let “his people” talk to J Lo’s “people”. He proved willing to sign the cheques that allowed an executive to hang out with Lopez, to learn what she was really like (far sweeter than her reputation, apparently) and then to encapsulate that in a flacon based on her body (a trick first tried in the 1930s when Mae West posed for a bottle based on her Hollywood curves).

It could have been a tacky disaster story. Instead, a range of JLo fragrances – which still sell, despite most fragrances having somewhat short “lives” – has generated cumulative revenues topping US$1 billion. The launch of Lopez’ first fragrance with Coty, J.Lo Glow is often attributed with reinvigorating the entire celebrity fragrance category.

The rumour back then was that Beetz identified J Lo or Madonna as his ideal collaborators. On the day Beetz and I meet there’s a faint rumour going around that Madonna is, at last, entering the scent scene. So who is the diva’s industry partner and how do you bottle Madge? “What are you talking about?” Beetz shoots back (It has since been announced that Coty’s Truth or Dare by Madonna, with topnotes of gardenias and tuberose, will launch at Macy’s New York on March 26 followed by an international roll out in May. “She was always on my list,” Beetz told fashion industry paper, WWD.)

Anyway, next up, for sure, are new launches from the Beckhams, plus Tim McGraw and Faith Hill recently announced the launch of a new Soul2Soul fragrance at their home in Nashville, Tennessee. And Lady Gaga will be gearing up to conquer perfume counters. For if you can sell 13 million plus albums worldwide and garner more than a billion views online and with 6.9million followers on Twitter, why wouldn’t you bottle it?

But it may come as a surprise to discover Coty does not do that. The world’s leading fragrance company does not make scent. Instead, it comes up with a concept then shops it out to the likes of Givaudan, Firmenich or IFF (none of these are household names) to create the liquid in the bottle, or in industry parlance, “the juice”.

Once the juice is right, whether floral, spicy, mossy, citrus, chypre or fougere (the latter perfume term translates as “fern”), Coty bottles it, packages it, promotes it and hopes that we buy it labelled Kate Moss or Playboy or Adidas or – coming soon – four Elite Model fragrances: Paris Baby, London Queen, New York Muse, Rio Glam Girl – tapping into the zeitgeist of Next Top Model TV shows. At the prestige end of the spectrum, there’s Bottega Veneta, Cerruti, Davidoff, Jil Sander, and a new scent by Roberto Cavalli. Coty has also developed scents with Sarah Jessica Parker, Halle Berry, Heidi Klum, Gwen Stefani, Renée Fleming and Celine Dion.

Flagged up in the Beetz Harvard study is a warning that the amount of travel endured by senior staffers threatens life/work balance; although, as the Rimmel London party ramps up, Beetz shows no sign of weariness. “I don’t force myself to be fit for the job, I just like it. I like the lifestyle. I like the rhythm of it. So I don’t know if I keep fit for the job or if the job is just shaped in the way I live,” he tells me. As to keeping everything spinning, he replies, “I think I balance it very well. I’m basically working around the clock. Work is life.” Let’s drink to that.