Sunday Telegraph Fashion Magazine | 20th March 2o11

Yohji Yamamoto

by Marion Hume

The question is not why is Yohji Yamamoto the subject of a major fashion retrospective at the V&A this spring, but what took so long?

For it is now 30 years since Yohji (always called Yohji, not Yamamoto by fashion insiders), along with Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garcons, stormed the bastions of French fashion. It was shocking.

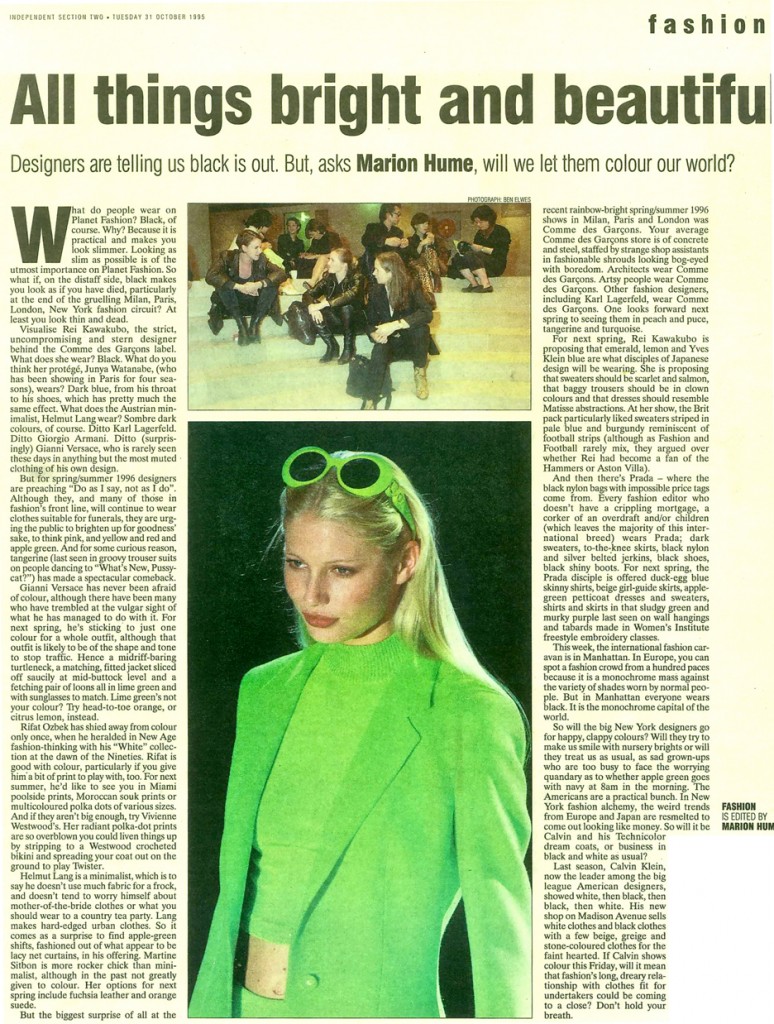

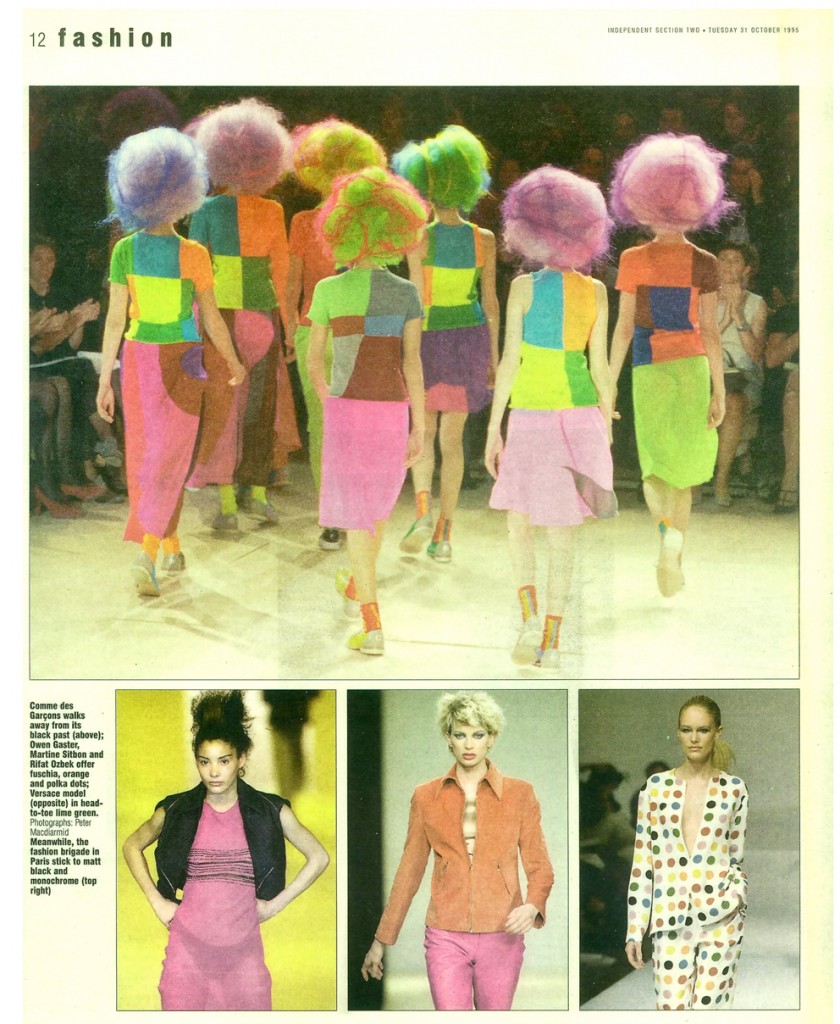

To say one is “shocked” can be used casually in fashion-speak these days. But in March 1981, the front row set were truly appalled. They were, already, in a jumpy mood before the first Yohji Yamamoto show began. The chill wind of President Mitterand’s newly elected socialist regime was blowing through the silken corridors of Paris fashion, where the motto is rarely Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite, but at least they expected to be on somewhat familar ground, to see more of the coquettish frills and furbelows of the likes of Valentino and Ungaro. Instead what they were confronted with was oversized, flawed, monochromatic, flat-heeled, gender neutral, asymmetrical, shabby looking clothes. “Is there a “yellow peril” on the horizon?” thundered Le Figaro. Not a line one could get away with now.

While the first to be accused of “Holocaust chic”, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo were not the first Japanese designers on the Paris fashion scene. Hanae Mori had established a gracious reputation for neat little suits, Kenzo had made his Jungle Jap shows into extravaganzas, Issey Miyake had been showing in Paris since 1973. But the storm caused by Yamamoto and Kawakubo didn’t die down, it got more fierce. By 1983, Le Figaro was still raging. telling readers, “this miserable-ism is not for you. Neither are these patched garments, nor these new rags, nor these fabrics tied hastily as tatters. Nor all this funereal black. Nor the livid make-up of decomposed women. A snobbism of rags that presents the future in a bad way.”

From the beginning, the British were more curious. Joan Burstein of Browns and the late Joseph Ettedgui of Joseph were quick to see the possibilities of the new wave. (Browns landed Comme des Garcons, the Joseph stores carried Yohji). British fashion students, who back then would travel by coach and ferry to Paris and beg, borrow or steal tickets to shows, were also early fans. Some recall finding their way to Yohji’s Paris studio after the first show and being shown textures and shapes completely new to the West. British Vogue also soon realised this was the aesthetic of the future, praising the designers of the “International East” “for their noblesse oblique, thunderstruck colour, marvellous new manipulations of print and texture.”

Part of the savagery of the initial reaction from the old guard must be attributed to the prejudice of those just one generation away from war. As for Yohji Yamamoto himself, he is defined by the circumstances of his birth, to a widowed mother, who would work 16 hours a day to raise him. In 1987, he said this in an interview with Sally Brampton, then one of the UK’s leading fashion scribes, now an agony aunt; “The reason my clothes (are the way they are) is because I have given up, because I desire nothing. Some people try to relate that to Buddhism but it has nothing to do with it. It is hard to appreciate what I say unless you were born in Tokyo in 1943 when the war was destroying everything. Success came just by chance. I never wanted anything. Like most of my generation in Japan, I didn’t want to do anything or be anyone, so I started to help my mother in her dress shop. I hated it.”

A lifelong love of rock n roll might seem to sound a lighter note (and led to a bizarre show where male models walked to “Ain’t Nothing but a Hound Dog” played on a bazooka), yet Yohji himself has been somber about “Americanization.” “We were fed American products but at a certain age you start realizing things. The problem was, who are the Japanese people?” he has said. “It is very difficult, even for us, to find out”.

Yet as time has gone on, Yohji has also, brilliantly and surprisingly, explored the aesthetic of Paris, where he sets up home for weeks every season (his mother comes too, to cook for him). Having first fought against the richness of haute couture, latterly he has subverted it. Who can forget Yohji’s catwalk bride with a gown so huge it swept the notebooks off the laps of those in the front row?

For all the memorable catwalk sensations, most of Yohji’s creations are rather plain, often navy and in industrial gaberdine which makes them seasonless. The same women who would not be seen dead in last season’s Prada happily boast of wearing “20 year old Yohji”, which explains why there is so little trade in Yohjis on the vintage market.

What his clothes have always explored is feminism. Never interested in coquettish appeal, his woman is always strong, although as he has concurred, “Most men do not like strong, independent women with their feet on the ground. Men don’t want women to be outstanding…. When women try to be real people there is tremendous pressure against them. I’d like to say hang on, keep trying.”

To do so, wearing timeless Yohji is a pleasure.