Tag Archives: retail

Anatomy of a Maison – Australian Financial Review

Anatomy of a Maison

The Australian Financial Review | November 2011

In the Medieval age, the sight of a towering spire signalled a city of splendour. Today, it is cathedrals of retailing that indicate metropolitan status in the global pecking order. The December 3 opening, not of another Louis Vuitton store – there are already 460 of those worldwide – but of a much grander Louis Vuitton ‘Maison’ (of which there are just 13) proves Sydney must be a very smart town indeed. Kar-Hwa Ho is the man responsible for the latest Australian opening, as well as such landmark stores as Louis Vuitton Singapore, housed on its very own island. Vuitton’s design director for the Asia-Pacific region tells Marion Hume about the new maison in the company of the brand’s Paris-based director of architecture, David McNulty.

A CATHEDRAL FOR A SECULAR AGE

“Is that a compliment?” asks David McNulty. “I suppose fashion houses are becoming architectural theatre in the way opera houses were and cathedrals used to be. For us, there is always a question of visibility. We cannot be tucked away. We must be seen.” So how big a footprint is needed for a maison? “About 2000 square metres” says McNulty. Walk-ins are welcome at the Sydney Maison, because busy George Street means there’s nowhere to park, let alone a space for your limo to wait. But what of those Vuitton stores where you can’t walk in? The line at the Paris Champs Élysées flagship store often numbers in the hundreds. “It’s really not good to have people waiting,” protests McNulty, revealing that staff serve hot beverages to waiting crowds and the company sometimes lays on transport to the other five Vuitton stores in Paris, “but everyone wants to go to that one because it’s the biggest.”

IF WE BUILD IT, THEY WILL COME

To semaphore to the customer that a maison is more than just a place to pick up a monogram wallet, it helps if the building itself is jaw-droppingly attractive and the Sydney Maison certainly is chic. “But we don’t own the building, which means there are restrictions,” explains Ho. Even without these, sometimes the most arresting designs don’t get built. All the architecture models that didn’t make it are in the Vuitton head office, including one of shining metal rods by Zaha Hadid. “One day!” says Ho, wistfully. Do the challenges of preserving history lead to better stores? Not always. “While we’re not interested in destroying heritage buildings, our original concepts are usually better,” says McNulty, who adds that, sometimes, keeping the history can go too far. At the recently opened Milan Maison, he says, “there’s a really ugly mural on the wall. Really ugly. It has a preservation order on it so we built a wall in front of it, so some archaeologist in the future can come in and find it.”

MAKING AN ENTRANCE

There is no grander gesture than empty space, given retail rents are charged by the (astronomical) square metre and here is 59 sq m of glittering floor over which you must walk to reach the central altar of retailing. Walking directly ahead, you enter a ‘fast lane’ leading to what is known as the ‘hot zone’. Here’s where you find the bag that stars in the latest advertising campaign. “The bags that are the ‘fashion moment’ can always be seen from the entrance to the store,” says McNulty. But does one turn left or right? “We don’t want to control that,” he says. “We want to convey to the visitor that there are many things on offer; leather goods, travel, the men’s universe, the women’s universe.”

FAMILIARITY BREEDS EXCITEMENT

The aim is to attract a customer who knows exactly what to expect yet is also in search of novel retail entertainment. Uniform across all Vuitton stores is a colour palette of caramel and toffee, a reference to the checkerboard Damier canvas of 1888, which in turn led to Louis’s son, Georges, inventing the famous monogram canvas of 1896. And, rather as a cathedral has a smaller, perhaps more opulent, altar behind the main one – this only visible to those allowed to venture behind a parclose – so too does the Sydney Maison have its hidden treasure: literally, given the watch and jewellery sales area is tucked behind the ground floor’s central selling station. “The aim is to create a more intimate area, away from the flow,” Ho says.

GOING UP

In all retailing, the challenge is to encourage traffic to upper floors. That’s been somewhat easier since 1857, when the first commercial passenger elevator was installed in a New York City department store. Yet the Sydney Maison has just one customer lift. “It’s not necessary to have more,” McNulty says. “What tends to happen is that people walk around and discover the store by themselves, including taking the stairs. A sweeping staircase – all steel substructure and timber veneer – is visible centre-left as you enter the Maison, inviting you to mount a stairway to heaven – or more precisely menswear first and then, on the second floor, ‘women’s universe’ for fabulous fashion by Marc Jacobs.

HOLLYWOOD GLAMOUR

As Gloria Swanson knew, one must be well lit. While the primary function of store lighting is to make sure you can see everything, at Vuitton, spotlights are trained on the hottest products just as kliegs were once directed on a movie star’s cheekbones. “Whenever we can bring natural light into the store, we do,” says McNulty, who adds that, despite a menu of lighting options, sales staff always choose the brightest setting. But in the ‘try rooms’ (this is Vuittonese for what you and I usually refer to as a fitting room), it is you who control the light, via a panel that allows you to check an outfit under the noonday sun, at twilight and by night.

DESIGN FOR MEN

Even in equal Australia, men rarely shop midweek, which risks a very empty floor. The solution: stick menswear on the first floor so women must go past it and thus might think, “I’ll get him a belt to soften the blow of all the stuff I’ve bought for me.” And when men do shop? “If a man sees a mannequin with an outfit on it, he could well buy the [lot],” says McNulty. Expect to see rows of mannequins. The primary male quest is for shoes. Your shoe guy wants to choose shoes, sit down, try them and buy them. So the chairs here (just one of 10 different designs in use by Vuitton) are the optimum height and tilt for trying on footwear. This is less of a concern in China where, “they have no problem waiting for a seat to be freed up; they’ll do it standing on one foot and they’ll even try clothes on without using a changing room,” McNulty says.

VIP

When spending a penny (as opposed to $4500 on the latest Tiger clutch bag), every customer is a VIP – given the VIP loo is for you. But there’s VIPs and VVIPs. Tucked into a corner of the second floor is an area code-named ‘constellation’, as in ‘star’. Here, those who require additional privacy can be accommodated behind a closed door. As for the old saying that common folk sweat, the rest of us perspire and stars glow, here’s why: the VVIP area has its own dedicated air con. It’s here that the most exclusive service – the chance to get a bag in shapes and leathers of your choice – will be offered. It’s called ‘haute maroquinerie’ in Vuittonese. ‘Hot maroc’ in Sydney-speak? Don’t say we didn’t warn you.

SECRET DOORS

While an exceptional sales associate cannot actually walk through walls, she can tap a mirror to reveal a door that allows her to reach the tills. Cash-and-wrap is hidden from your view, “although we have to make sure that this works well with the flow of the selling ceremony,” says Ho. “You don’t want your salesperson to disappear for too long with your things while you are sitting around waiting.” But what about disappearing with one’s credit card while, even in restaurants, they bring the machine to you these days? “Mostly, people don’t mind,” Ho says. “But in Asia, customers follow their salesperson to the till. People pay cash and need a secure area to count it.”

ECOLOGY

Everything is as ecological as possible, from the certified woods you can see to the basement unpacking area you can’t, where paper and cardboard are stored. “Our Guam store is powered by solar panels,” Ho says. This not an option for Sydney where the building is rented.

AUSTRALIANA

While big-brand stores look somewhat the same around the world, Vuitton makes the effort to help shoppers remember what country they are in. In Auckland, the store features model lambs created by a Kiwi. In Jakarta, there are Indonesian lamps and stools. So for Sydney? The eagle-eyed will spot eucalyptus motifs played out in wood marquetry. Coming soon – although not in time for the opening – LV monogrammed surfboards should provide a clue.

WINDOW ON A NEW WORLD

Windows are an invitation, and a global mega-brand requires lavish displays. “From our standpoint, that means providing the right space and lighting and access,” says McNulty. The secret to quick changes? Panels that can move in and out and doors big enough to accommodate a window dresser carrying a zebra. That is not a joke. The windows in London’s Bond Street currently feature a herd of life-sized African fauna.

The Secrets of Zara’s Success – The Daily Telegraph

The Secrets of Zara’s Success

Classy, well-tailored, cheap-and ethical. Can the world’s favorite clothing store do no wrong?

by Marion Hume

The Daily Telegraph | June 22nd 20011

How do we love thee, Zara? Let us count the ways. Some numbers make a good place to start: a company founded on just €30 is now worth an estimated €32 Billion. Last week its parent company, Inditex, of which Zara represents over 60 percent, declared an 11 percent rise for the first quarter to €2.96 billion.

Translated, Zara was coining it while other retailers spent January to March moaning about recession and rising production costs. Next quarter’s financials look set to be more spectacular, if the response to the £49.95 blue dress worn by the Dutchess of Cambridge after her wedding is anything to go by.

So why do those as diverse as Kate and the business brains at Harvard which recently commissioned a study of the brand love Zara? Here’s a top 10.

1 The designs work in normal life.

Walk into a Zara. See anything you like? Thought so. A bug reason for this is that there is no Zara “style” – its appeal is broad. Yet you won’t find everyone else in the office in the same dress, and here lies the first clue to its supremacy. Although Zara may run up 30,000 copies of an item, supply is spread thinly over its 5,157 stores in 81 countries, plus its online shop. Scarcity plus realistic design equals kerching! at the cash till.

2 Fast Response to city-specific trends

A new white jacket arrived at the Manhattan flagship store. But customers passed, telling sales staff that New Yorkers prefer cream. A system is in place for retail staff to transmit such information straight to the design team at Arteixo, a tiny town in north-west Spain. Within a fortnight, a much bigger consignment of cream jackets had been dispatched to become a sell-out on 42nd street.

3 It’s mass with class

That Zara has its headquarters in Spain is significant. While influences are global, Spanish customers have always liked curvy cutting to flatter a proud bearing. The result is that Zara tailoring seems higher quality than other in this price range (blazers start at around £49.99), and styles are on-trend as opposed to too trendy.

4 A signifier of stylish city

A Zara store opening signifies a city has arrived sartorially. “Thank God, we won’t be a third-world fashion country any more,” said a Sydney- residing fan at the first Australian opening in April. Such was the delight down under that crowd control barriers had to be maintained for weeks. Those in Cape Town, Taipei and Lima may be equally excited.

5 Intrigue…

Just as consumers are driven by scarcity, so the press is intrigued by the greatest fashion story never told. Inditex founder Amancio Ortega, 75, the son of a railwayman who is now rated as the ninth richest man in the world, has never given an interview- and probably never will. Next month, he hands over to his equally taciturn second-in-command, Pablo Isla.

6 A Brilliant brand name

Those launching brands seek short, sharp names that work in every language. Yet this four-letter word was an accident. From 1963, Ortega’s company, which manufactured nightwear, was called Confecciones GOA (Amancio Ortega Gaona’s initials backwards). In 1975, he started to sell direct to public through a little shop in La Coruña and decided to call it Zorba. But the owner of a nearby bar of the same name protested. A new name had to come from the letter moulds already cast. Ironically, Spain is the only country in which Zara is pronounced not “Zah-rah” but “Tha-ra”.

7 The Green Frock

Inditex ups its eco rating by using wind turbines and solar power in its headquarters. Recaptured energy is even redirected into the steamers that press every garment. Items are despatched in battered boxes, which are reused and then recycled. Bicycles are provided for workers to whizz around inside vast warehouses. Green, yes- but is also makes good business sense because it saves money.

8 Seductive, sustainable store design

Store design is really working when you are too busy shopping to notice. Zara stores are built to seem airy and light-even on a busy Saturday-while the current in-store look, closely inspired by Prada, is for squadrons of mannequins gathered together to show off the season’s many looks. To decide on how its global stores should appear, Inditex tests entire “streetscapes” of prototypes for new-look Zara stores within a vast hanger at Arteixo. The radical Rome store, the prototype for all new builds, is on target to receive a platinum standard in Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), a seal of sustainable architecture that is one of the most demanding of its kind.

9 A hooray from Harvard

The ultimate business plaudit is a study by Harvard business school. What do the money men love? That Zara turns the fashion system, which usually starts with the whim of a designer, on its head, by putting the customer at the heart of a unique business model. But there is a downside: for this model to thrive, Zara’s “designers” are strongly “inspired” by the creations of others, who are neither acknowledged nor paid. Not for nothing had Daniel Piette, fashion director of Louis Vuitton, described Zara as “the most innovative and devastating retailer in the world”.

10 Ethics Appeal

Inditex is intelligent in its generosity to charity. Following the Haiti earthquake, Inditex sent €2 million of emergency reconstruction relief as cash, not clothes. You might think that those who have lost everything need clothes, but as a result of other fashion giants sending these, local clothing industries have never recovered, leading to a greater dependency on aid, rather than trade.

In Spain, some stores’ employment practices make it possible for those with mental and physical disabilities to join the workforce.

But let’s hold back on awarding Zara that tenth love point for now; a somewhat murky supply chain makes all fast-fashion tough to love. Potentially vulnerable garment workers manning sewing machines in countries such as Bangladesh, Turkmenistan and Pakistan. In Zara’s favor, though, much of its production is in factories it owns in Spain, meaning it can guard against the scary labour practices that haunt the high street.

However, you can help by letting them know how much that matters and even that you are prepared to pay a little more and wait a little longer to ensure fashion is fairer.

Remember how they listen to customers asking for cream jackets? Use that system to ask for clean jackets at the cash till or via zara.com. You could also suggest that Zara provides “swing tags” that detail your garments journey to you.

Why would the world’s biggest fashion force care what you think? Because Inditex has conquered by putting the customer at the care of the story. Do speak up.

Kiss and Sell, Sir Philip Green – AFR

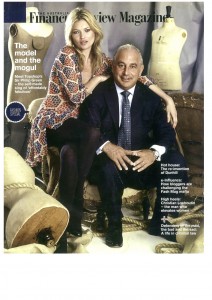

KISS AND SELL. SIR PHILIP GREEN

by Marion Hume

The AFR Magazine September 2010

The self-made king of affordably fabulous has the retail touch: Sir Philip Green ships about 150 million garments a year through ‘cheap chic’ outlets such as the Topshop chain. He’s worth about $7.6 billion and is still working

on how his businesses can adjust to a new consumer embracing social media

Sir Philip Green doesn’t waste time. My allotted slot with the global king of affordable chic is at 1 o’clock, and at 12.59pm, after ice water and coffee has been served in the plush reception area outside his office (pale carpets, swanky sofas, Jo Malone scent in the loo), the door swings open and here he is; pin-neat grey suit, pristine white shirt open at the neck. Two buttons, no tie; silver swept-back hair shimmering with the sheen of a shampoo commercial; tanned skin positively glowing. In other words, the absolute picture of a 58-year-old, self-made man worth about £4.43billion ($7.6billion), whose Monday morning commute from the family home is by private jet from The French Riviera.

Green is famous for the fact he pulls no punches and answers his own phone (not some new-fangled device but an old Nokia; he has a stockpile of them). Want to know about the ethics of the rag trade – a tough call for a man whose fortune rests on cheap chic manufactured in the murkier corners of the world? He faces it head-on, doesn’t blink. The only thing his VP of communications has suggested is that I don’t ask for his life story “because the risk is, that’s your time gone”.

I decide not to ask about his plush pad in Monaco, a tax haven, either. As Green has told reporters before – not angrily, just firm – he pays tax in Britain. He does not claim non-residency. (However, that Britain’s ninth-richest person has received hefty dividends from Taveta Investments, which is in the name of his Monaco-based wife, Lady Tina, has been widely reported; less publicised is the fact that he has not done so for the past four years.)

In Australia, Green’s best-known brand is Topshop, which, famously, carries a collection by Kate Moss and sells in Incu in Sydney, as well as in New York, Paris, Hong Kong. It also sells in The Department Store in Takapuna, New Zealand, where, when the brand arrived last May, the first sale was at 7.03am and it took four hours to clear the queues around the block.

Green’s Arcadia Group, privately owned by Taveta Investments, also numbers a score of High Street chains not present in Australia, as well as vast and growing e-commerce sites. The brands operate in more than 30 countries across Europe, the Far East and Middle East. Pretax profit for 2008-09, the most recent data available, was £213.6 million, up 13 per cent from £188.9 million. This in a recession still being felt deeply in Britain.

Those MBAs that have become fashion’s favourite accessory are not for this high-school dropout. “There’s parts of it you can learn, which are probably the mechanical pieces,” the billionaire concedes. “But you can’t learn to have a good eye. You either have it or you don’t.” Of course, Green has it and his decisions are snappy. “I’m doing this on the run, I’m turning up, show it to me,” is how he explains his M.O.

“So just now, I was just going through ladies dresses for Christmas; before that, knitwear. When you’ve finished, I’m going to see Kate Moss about her collection. Do I chuck stuff out I think won’t work? Yeah. I saw some knitwear this morning. Didn’t like it on the hanger. Then I’m looking at dresses and I asked [myself]: ‘If this was your last bet, is that where you’d be putting your money?’ In my mind, you weigh up the risk/reward box. I said, ‘If you want to buy a dress that sells at £40, and you want to buy a dress that sells at £70, buy 5,000 of the one that sells at £40, and 600 of the one that sells at £70. It’s not negotiable – unless they prove to me the reason why they think I’m wrong.”

Green hails from London’s Croydon, a suburban sprawl better known as the birthplace of Kate Moss, whose Topshop collections reward her with an undisclosed fee, plus a percentage. As for the ‘Sir’ bit, no one from Croydon, where there are no stately homes or rural acres, has one of those inherited toff titles. Sir Philip Green’s was earned, bestowed for services to business. He was born not rich, not poor. His parents ran garages, electrical shops, property. When he was 12, his father died, his mum carried on and he helped out in the business during school holidays until he left school at 16 and started out on his own. He hawked cheap shoes from China, then jeans. Then he bought up some struggling shops, was making money and, well, let’s fast-forward to 2002, when he acquired the Arcadia Group, including the Topshop chain, for £850 million – or we will, indeed, be here all day. He acquired British Home Stores, rebranded now as Bhs, before Arcadia but has failed in three attempts to grab the High Street prize that is the giant Marks & Spencer.

No surprise that the king of the hill is both liked and loathed; he’s liked by Kate Moss and Naomi Campbell – both of whom call him ‘Uncle Phil’ – and by most key staff, who praise his unerring instinct, photographic memory and ability to helicopter in (often literally) and sort things out. Green is loathed, or more accurately envied, by a certain segment of the British tabloid press, which deems it obscene for a man who has made his own money to relish spending it, hence snide asides about the Gulfstream jet, the pad in Monte Carlo, the family cruises aboard the 63-metre yacht, Lionheart, while the Greens’ now-adult children, Chloe and Brandon, weigh anchor nearby aboard the 33-metre Lionchase.

Sir Philip and Lady Tina throw lavish parties, hiring Beyoncé or Rod Stewart to entertain their guests. The list of charities supported by a spectacularly fat wallet is long, so we’ll start and end with how Green first met Moss when he paid £60,000 for a kiss in a charity auction. Aware how seedy taking the prize would look, he donated it to the underbidder, Jemima Khan. Images of the girl-on-girl smooch went around the world.

You won’t, by the way, find many of the fashion pack scoffing at Green, especially since it was under his ownership that Topshop, once notorious for rip-offs that stole designer ideas, turned into a fulcrum of creativity. For almost a decade, Topshop has been funding New Gen designers in the early stages of their careers, plus (brilliant this) every season, Green and team set up what has to be the world’s most glamorous soup kitchen to feed and water (and champagne) the international fashion pack during London fashion show season.

Green takes plenty of time off – summer on the Med, winter in Barbados, fitness breaks in the US in between – but that isn’t to say he switches off. “I went walking in Arizona last week and a lot of the time I spent thinking, ‘How can we do things differently? How do we adjust to the new world we live in?’” he says. “We’re in an over-shopped world, so you’ve got to create more theatre, more fresh … You’ve got young kids now who spend their time on this Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and every other form of communication on the planet. You have to be clever, smarter, newer …”

Back when Green was flogging his first cheap shoes, the consumer didn’t care about workplace practices, ethical fashion, carbon footprint. Arcadia owns none of the factories in about 60 countries – including China, India, Mauritius, Romania, Turkey – that supply its stores, although, of course, its management and staff are acutely aware that proof of something ghastly, like child labour or mistreatment of women, could threaten everything. Arcadia funds what is probably the global clothing business’s biggest compliance team, last year alone staging 1,044 factory ethics audits, carried out by independent bodies trained not just to look but to ask, and in such a way that those on the economic margins fearful for their livelihoods are able to respond.

“When you’ve got a business directly employing 45,000 people, therefore probably indirectly [benefiting] 150,000 with families and kids, you know everyone is watching,” Green says. “I want to sell the best products I can, at the best price I can, in the best quality I can and there’s no point cutting corners, because you’ll get caught. You’ve got to educate the people who work for us that we want to do things in the right way. We run a very professional, proper ship. There’s no dodging round.” In 2009 alone, the group rejected approaches from 37 new factories until work practices were brought into line. Thus, the consumer can enjoy fast fashion, confident that it has been produced fairly, although there are still improvements to be made. “I don’t want to be a manufacturer,” Green says. “I finance them; I lend them money; I help them buy machinery; I help them build factories but I don’t want to be the owner because I don’t live there. I can’t put my hand on my heart and say to you I know about every single worker. We’re shipping 150 million garments a year. I can’t look you in the eye and say I can guarantee every single piece because someone’s got to go to Timbuktu, make it, inspect it, colour it, ship it. But, hopefully, we are doing as good a job as we can.” Arcadia also has an in-house ‘police’ force, the Fashion Footprint Group, which has a clear mandate to align social responsibilities with business practice, encompassing everything from recycling to taking a stand on the mulesing of Australian sheep. (From the end of 2010, Arcadia will not work with wool suppliers who practice mulesing against fly strike, irrespective of the use of pain relief.)

But enough of the worthy stuff. What Green really wants to talk about is shopping, knowing that, on the way here, I’ve popped into some of the stores. “What didn’t you like?” he demands. Eyes locked, I say I found the flagship Bhs store hard to navigate. “In which way?” The first floor didn’t entice me. “OK, that’s because you walked up [and] so hit childrenswear first. There’s always a struggle and a debate how we tell people what is on each floor. We’ll fix that.” On to Topshop, where the crowds and the chaos and the neon may be heaven on a stick to Sir Philip and every teenager – “if you took 20 CEOs to Topshop, they’d be dishonest if they didn’t say, ‘Wow, this is a real retail experience’,” he beams – but I found it such a jumble and so packed. “Jumbled up in which way?” he booms, “and who complains if it’s busy? Put that on your tape! That’s what those retailers want!”

Of course, what Topshop has, which fast fashion competitors such as Zara and H&M don’t have, is Kate Moss. (H&M did have her, but dumped her after an alleged brush with drugs earned her the nickname ‘Cocaine Kate’ in 2006.) As the myth goes, Kate moseyed up to ‘Uncle Phil’ in a restaurant a couple of weeks after the paid-for pash at the charity do, said something along the lines of, “We’re both from Croydon, let’s do business together”, and it’s been the music of the tills ringing ever since. But it wasn’t quite like that. Negotiations, apparently, were protracted, especially as Green, used to people snapping to attention, needed to be convinced a fashion princess could do things his way. “To be honest with you, at the time, without being conceited, I think it was actually pretty brave because a lot of people had dropped her,” Green recalls now. “People said to me, ‘Are you sure?’ And this is back to instinct, because that told me ‘Good moment’. Topshop had never had a ‘Face Of’ so it was a complete departure. Part of being an entrepreneur is risk and my attitude was, if I’m wrong, what’s the worst that’s going to happen to me? It’s not going to threaten my whole business.”

Actually, it has lifted it hugely. Moss is helping to push the image of Topshop to a whole new level. “It would be fair to say it [lifted] the profile,” Green says. “It’s never been a huge piece of business, and it was never planned to be a huge piece of business. It was about her brand, our brand coming together and you hit the right mood, the right moment. But at the end of the day, the product can’t lie. The merchandise has got to be great. You can’t kid people, and that’s what’s key.”

“Of course, Kate Moss helps,” says designer and retailer Karen Walker, of The Department Store in Auckland. It was Topshop that suggested forging a deal with the hip Kiwis of Takapuna, following successful partnerships with Opening Ceremony in New York, Colette in Paris, Laforet in Japan and Lane Crawford in Hong Kong. Walker says, “The volcano [in Iceland this year that disrupted air travel worldwide] interrupted our initial deliveries, so what we ended up doing was a one-weekend preview, which sold out, then we closed down for two weeks and the second opening was even bigger. We’re the custodians of the brand in New Zealand and both companies, long term, will benefit from the mutual experience.”

The brand made its Australian debut in October 2009 at Incu, transforming a little-used upstairs space above the Paddington store into a must-shop destination. “It’s provided us with a whole new customer base,” Incu director Brian Wu says. “Now, customers can go upstairs to our Topshop area to buy pieces to wear on the weekend and then head downstairs to buy a jacket they have been saving up for, which will last them for many seasons.”

As to why people somehow go more crazy for Topshop than its key competitors, specifically Zara, Green puts it thus: “Zara’s is a great business. I admire and respect it and I’d love to own it. We’re in a slightly different business, though. We’re more edgy. Mr Ortega [Amancio Ortega, Zara’s founder] told me one of his favourite shops in the world is our Oxford Street store, and if you’re in our industry, it would be.”

Later, we’ve moved on to chat about a schools program dedicated to fostering entrepreneurial flair when there’s a sudden ‘knock-knock’ and, “Sir Philip, your 1.30 is here”. It is 1.28pm. “Hello, Naughty,” he calls out through the open door, “with you in a minute.” “Hi Uncle Phil,” Kate Moss says as she pops her head around the door, then he’s back with me, 100 per cent focused, wrapping things up before we shake hands. And then Moss comes in, shakes my hand and we’re done. So it’s a minute later, back in the snazzy reception that the true power of Sir Philip Green hits me. Yeah the billions and the retail turnarounds in record time are impressive, but lordy! What about getting a supermodel to turn up two minutes early! ■