Tag Archives: Yves Saint Laurent

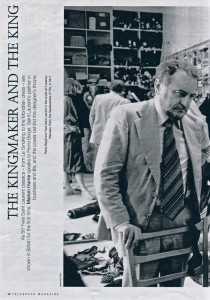

The Kingmaker and the King – Telegraph Magazine

Rainbow – Australian financial review

by Marion Hume

How can you copyright a colour? The notion seems ludicrous. Imagine some swaggering luxury goods titan looking up at a rainbow and pronouncing, “I want red for this brand, orange for that brand, worldwide usage for yellow, all rights for green and I’m banning anyone else from blue, indigo, violet.”

Yet who owns what tone has become a hot topic. A while back, I was asked to write a letter in support of the French shoemaker, Christian Louboutin’s right to red and I was happy to do so. Louboutin’s red soles are a potent brand signifier. So no wonder he saw red and sued when Yves Saint Laurent offered red soled shoes too. The presiding judge found against him noting that no one designer should have a “monopoly” on any color. At time of writing, the case is on appeal.

Louboutin became associated with red by accident. He thought the black soles of his first designs for high heels looked depressingly dull so he grabbed some nail lacquer and added D.I.Y. pizazz. Does he own red? Powerful forces rallying to his support certainly hope so. Tiffany & Co. has filed something called an amicus curiae because if Loubi loses, who owns the blue the jewellers have been using since 1845?

There’s no question, surely, that Hermes owns orange. Yet like Loubi-red, Hermes orange was an accident. Until the end of the 1930s, the company’s packaging was brown. But under the Nazi occupation, paper stock became near-impossible to find. Someone heard of a cake shop that had had to close. The sunny packaging in which people had carried home gateaux in happier times was available because other luxury marques thought it too vulgar. And so orange came to signify hope, then chic and now – certainly if it is me who is the lucky recipient of an Hermes gift – absolute joy.

Hermes orange has gone even further, to the point that it is synonymous with Paris itself, for orange = Hermes = Parisian chic. Yet when you look at the fabric of Paris, it isn’t orange of course, it’s dove grey or in the watery light of early spring, the most ravishing lavender. And hardly anyone in Paris ever wears orange, with the exception of the Australian, Marc Newson, who has a penchant for vivid windcheaters.

Elsewhere, when nature, light and beautiful architecture can’t be called upon, a splash of bright paint can be transforming in how we see a city. I’ve never been to Tirana, Albania, among the most isolated capitals in Europe. But my interest was piqued when the mayor decreed that brutalist architecture – and thus citizens’ lives – could be improved with bold stripes of yellow, green, blue and red applied all over the tower blocks. Similarly, in the favelo of Rio and the slums of Nairobi, painting rundown buildings in vibrant colours is starting to have the effect of cutting criminality, which it turn gives locals more power over their lives.

This isn’t new to me. In 1851, a social experiment took place in a notorious London slum. When a row of cheap little terrace houses went up, each was rendered and painted a different colour to see if poor people might behave better if they lived in pretty houses. As my neighbours and I quip today, as we stand outside homes still painted primrose, pistachio and rose, we do. We also know our street brightens the day of many who walk through because they stop and tell us so. Colour is cheerful. Should fashion designers ever get ownership of it, then? I think, sometimes, yes. But given my suspicions that there are luxury goods titans out there would love to project brand logos onto the moon if we let them, we must stay vigilant. We hold the monopoly on how we colour our world.

A guide to the 1970s

A guide to the 1970s

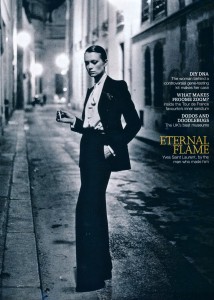

Think the Seventies was all about the maxi-dress? Think again. From slick pantsuits to the delicate crepe dresses of Yves Saint Laurent, via the punky pins of rockers’ garbs, this diverse decade has influenced a roll-call of designers for autumn.

BY MARION HUME | 05 OCTOBER 2010

Why are Seventies styles all over the stores right now and, judging by the current round of catwalk shows, staying around next season? Given the original styles were so diverse, there is no short answer. But try these explanations for starters.

Silhouettes and soundtracks

It’s easier to spell out the vast range of looks through sounds of the Seventies. Think Isaac Hayes’s theme from Shaft ; now think Slade; now the Jackson Five; Abba; Rod Stewart; and Bob Marley. If you are old enough, was it Ziggy Stardust segueing into The Sex Pistols for you? Or David Cassidy to Bruce Springsteen? T-Rex to the Jam? Cher’s Gypsys, Tramps and Thieves to The Hustle ?

“The fundamental difference now is the focus on luxe,” says Bridget Cosgrave, fashion director of Matches. Her Seventies memory? “My mother wafting around in silk kaftans to Donna Summer’s I Feel Love .”

It’s all about your mother

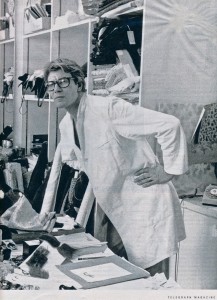

The most influential collection of the Seventies – and as important now – was Yves Saint Laurent’s reinvention of memories of his mother, Lucienne, in the crêpe dresses, palazzo pantsuits and platform sandals she wore in the Algerian sun when he was a boy in the Forties. Unfortunately, those styles reminded fashion scribes at his 1971 show of the Nazi occupation of Paris. But just as the old guard hated the collection, the young, like Paloma Picasso, adored it. Those silhouettes were worn by Linda McCartney, the late mother of Stella McCartney, who is in turn now influenced by her mother. As is Phoebe Philo by hers.

“It’s striking how a crop of principally British, thirtysomething designers are re-exploring the easy, chic clothing their mothers once wore,” says Penny Martin, editor-in-chief of the trendy magazine, The Gentlewoman . “Several of them – Phoebe Philo at Céline and Stella McCartney, for instance – are now working mothers themselves and recognise the need for clothes that don’t make them look idiotic. The palette – caramels, flesh tones, pragmatic black and white – as well as generous silhouettes inspire confidence and warmth in those wearing them. Women genuinely look and feel great in these clothes.”

Teenage kicks

Many designers were teenagers in the Seventies, and you never forget your first fashion love. A 17-year-old Tom Ford moved to New York City just as Halston was at his height. At Ford’s womenswear comeback this September, “the ambience of the showing was pure Halston,” says Kate Betts, contributing editor to Time .

Marc Jacobs was familiar with the best designs of the Seventies; aged 15, he started working at Charivari, then Manhattan’s most cutting-edge boutique. Meanwhile, Stefano Gabbana was yearning to afford more than just the stickers at Milan’s Fiorucci. Albert Kriemler now helms his family’s label, Akris. When he was a teen, his father was producing clothes for the ultimate Seventies label, Ted Lapidus – clothes which influence the slim silhouettes in mustard and burgundy in Kriemler’s collections today.

First love never dies for the shopper, too. In 1976, Mimma Viglezio looked so great in her Lee Cooper burgundy corduroy flares, she won the “Miss Arse” competition at her Swiss high school. “It really was called that,” insists the former executive vice-president of Gucci Group, who is now a leading luxury world consultant, adding, “I still love high-waisted flares. When you are not 16 any more and your tummy is not quite so flat, a high waist is more flattering than risking a muffin top!”

Punk

Karen Walker, the designer, was in Auckland rather than New York when CBGB and Studio 54 were at their zenith. “But I love the Seventies as the last age of underground hedonism,” she says. Although the influence of punk has been enormous – there were studs, leather and zips at Balmain last week, set against the sound of Sid Vicious doing My Way – it was a fashion blip at the time. In 1977, Zandra Rhodes somehow made safety pins sweet, but real punks wore Millets and DIY, which is why the rare few who could afford Westwood/McClaren items have since sold them for a fortune.

The thrill of the old

It was in the Seventies that fashion’s looking-backward-to-go-forward dynamic kicked off. In 1971, Cecil Beaton curated an exhibition at the V&A called Fashion, An Anthology , which celebrated styles of previous decades and had the knock-on effect of making wearing vintage smart.

“Today, dealers charge up to £100 for rare and beautiful clothes in perfect condition,” wrote a surprised Georgina Howell in 1975. “Now, in London, you can find a whole range of fashion within a stone’s throw – tweedy, ethnic, Hollywood, classic, glamorous, executive, nostalgic…” Should you be in search of Seventies originals, you’re too late; designer scouts long ago scooped up “inspirational” YSL pie-crust cuff satin blouses. Look for lesser-known labels such as Stephen Burrows or bang-on-the-ethnic-trend Mexicana – Princess Anne packed a Mexicana gown for her 1973 honeymoon.

Celluloid heroines

So to answer how to get the look, well, which look exactly? To narrow it down, you could rent the right films. Everything Julie Christie wears in Don’t Look Now (1973) looks right. Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), although set in 1937, features Faye Dunaway looking very Céline. If you want a Gallic twist, try the early work of French actress Dominique Sanda.

Then there is Lauren Hutton, who began the Seventies as the multi-million-dollar model girl next door, and ended it looking as if she was about to be crushed by the hard-edged Eighties. American Gigolo (made in 1978, released in 1980) is best remembered because Richard Gere’s wardrobe kick-started Giorgio Armani’s dominance in menswear, but it’s Hutton’s flicky hair, blouses and leg-elongating nude mules that are so very now.